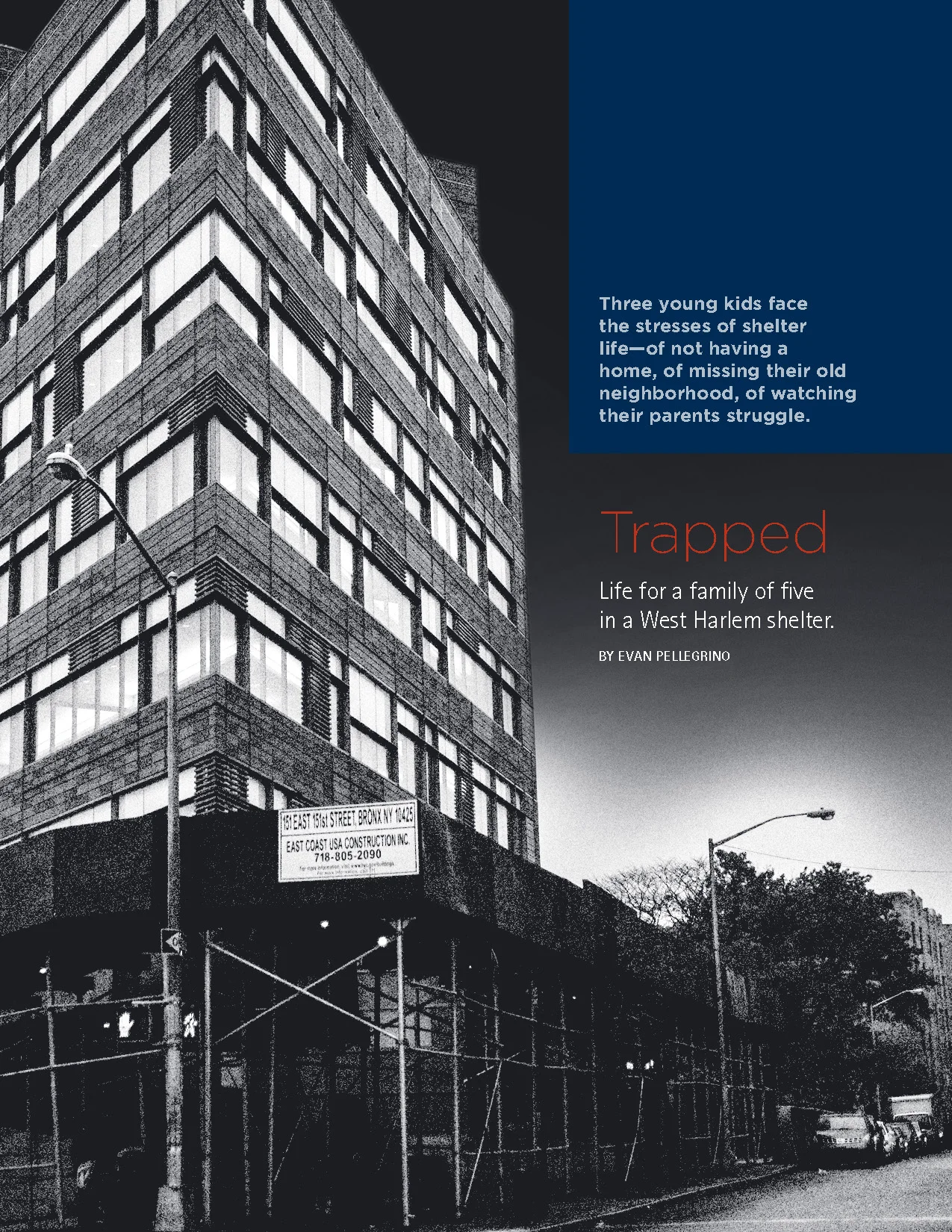

Trapped:

Life for a family of five in a West Harlem shelter.

By Evan Pellegrino

Shortly after moving to the West Harlem shelter at 30 Hamilton Place, Naiquan Pritchett, 34, and his fiancée, Giffany, started noticing changes in their children. Their 1-year-old daughter, who had recently spoken her first words, became uncharacteristically clingy, demanding constant attention and holding. Their 6-year-old son started throwing tantrums, crying and throwing himself on the floor, sometimes breaking cherished toys on purpose. Their 3-year old daughter, who once joyfully shared every detail of her day, became increasingly silent and reserved.

“She just shuts down. She won’t talk. She won’t respond,” says Pritchett. “There used to be times I couldn’t even get her to be quiet. She would be so talkative about everything. She would tell me about what she did that day, telling you about all she saw and experienced.”

For Pritchett it’s clear what’s happening: the stresses of shelter life—of not having a home, of missing their old neighborhood, of watching their parents struggle—are getting to his kids.

Last May, Pritchett’s family lost the Bedford-Stuyvesant apartment where they had lived for six years after their landlord got in trouble with the city for renting illegally. Pritchett had recently lost his job at a moving company. Evicted with nowhere to go, he took his family and all the possessions they could carry to a temporary shelter where they spent the night. “It was unexpected,” Pritchett remembers. “I had nothing saved.”

The next day they went to the Department of Homeless Services’ Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) intake center in the Bronx. There they began the exhaustive evaluation process required to receive housing in a city shelter.

Pritchett says his family was denied long-term shelter three times for not having the right documents. After each denial, they returned to an overnight shelter, then went back to PATH to start the process over again.

At PATH, they would wait for several hours to meet with various caseworkers as the children became increasingly hungry, tired and cranky. Once, his children refused to eat the baloney sandwiches the center provided. They began crying, saying they were hungry. Overwhelmed, Pritchett decided it was worth risking his spot in line to leave the center and buy food for his children with some of the last of his cash.

In the three weeks it took before the city approved his family for a long-term shelter, they moved between temporary shelters four times—a situation Pritchett describes as traumatic. “My kids didn’t understand,” he says. “It hurts I have to put my kids through a situation like this.”

The six-story family shelter where Pritchett, Giffany and his children now live is one-and-a-half to two hours on the subway from their once longtime neighborhood and home. The shelter once housed single adults for short-term stays. Today, parents and their children crowd into rooms with kitchenettes and an attached bathroom where they live for months at a time, sometimes years. Pritchett’s family has a room with a crib and two beds—one bed is shared by his son and daughter, the other by Pritchett and Giffany.

The residents’ complaints are common: the deteriorating conditions of the building; the lack of space; the services they aren’t receiving. Pritchett makes a point to keep to himself. He doesn’t trust the staff or other residents—some of his possessions have gone missing. Besides, families aren’t allowed to have visitors to their rooms, not even other shelter residents. This makes it impossible for families to help each other in the shelter. “I can’t even get someone to babysit for me if I have to run out,” says Pritchett.

Pritchett can rattle off a list of other dissatisfactions: the broken stove he reported to the shelter months ago that still isn’t fixed; the mold in the shower; exterminators entering his room without his permission, disregarding his concern that the poison they use could hurt his kids; a refrigerator shutting down and spoiling his family’s groceries, forcing him to use his remaining cash replacing the food.

But it’s the impact on his kids that hurts him most. “It’s tough because they no longer have the freedom they had,” he says. “They get bored quick and easily. They complain.”

Pritchett and Giffany have done what they can to help their children maintain a sense of stability and normalcy. A family friend drives Pritchett’s son to school in Bed-Stuy. It’s an hour drive each way, but it lets him stay connected with friends and teachers from his former neighborhood. Pritchett enrolled his older daughter in a daycare program he learned about from a woman handing out business cards on the street. It costs him $125 each week, a splurge he justifies saying that the opportunity for his daughter to socialize and play with other children is priceless.

Pritchett looks after his youngest child himself, while her mother sleeps after working the graveyard shift at a McDonald’s in Brooklyn, a job she’s held three years.

Though the shelter houses more than 150 families, it doesn’t have a play space for children to run around in or do homework. This is typical of many of the city’s family shelters, a number of which lost recreation programs due to funding cuts over the last decade.

Pritchett finds himself constantly scolding his kids for playing too loudly. “They’re limited to their surroundings and a small space of floor to play with their toys,” says Pritchett. “They’re not having the liberty to be themselves. My kids can’t be kids. I don’t want them to be stuck in this shell.” A park near the shelter is the one place the children feel free to be loud, to run and play in open space. But the onset of cold weather is foreclosing that option.

Pritchett says the stress is taking its toll on his relationship with Giffany as well. Pritchett and Giffany have known each other for 12 years. But these days, he describes their relationship as two people who pass each other by.

When she comes home from her commute from work, which some days takes up to two hours, she goes to sleep as Pritchett prepares their children for the day. On the rare occasion that they are both awake and together, Pritchett and Giffany find themselves increasingly in conflict. They agree on one key thing—that they need to get their family out of the shelter as quickly as possible—but they find themselves arguing more and more about how to make that happen.

“In a sense I feel trapped,” says Pritchett. “Sometimes I’m ready to give up. I’m ready to throw in the towel and walk away.”

SELECTED STORIES

“It hurts I have to put my kids through a situation like this.”