April 5, 2017

Restoring Parent Trust in Harlem’s Beleaguered Public Schools

By Clara Hemphill and Ana Carla Sant’anna Costa

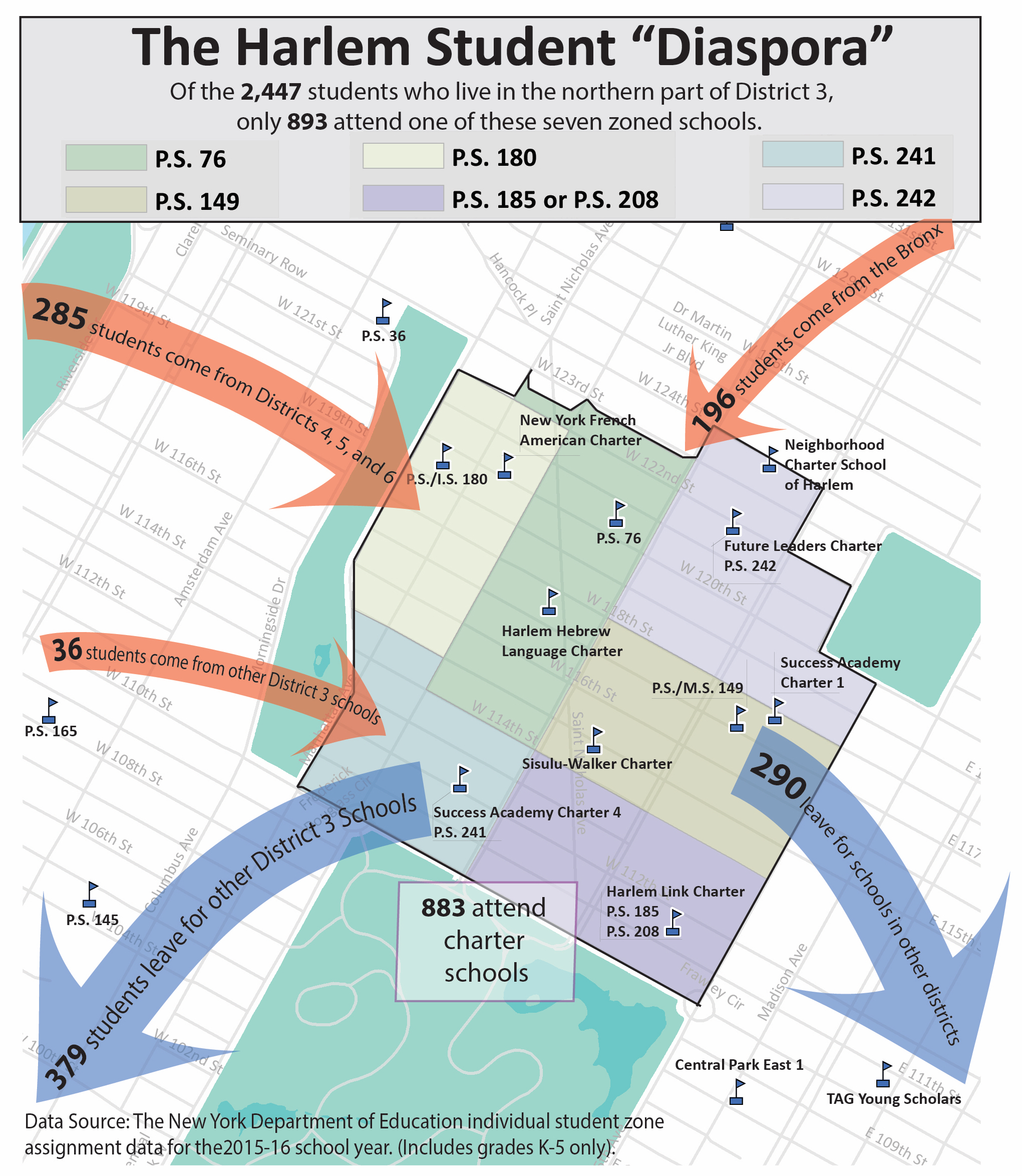

Stand on the corner of 116th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem early on a school day morning, and you’ll see a steady stream of children leaving the neighborhood by bus and subway. Some parents call this daily exodus the “Harlem diaspora.” They may live in the neighborhood, but they don’t necessarily send their children to their zoned neighborhood schools.

The hemorrhaging of students over the past decade has left many of the traditional neighborhood schools with declining enrollments and shrinking budgets. Five of the seven zoned elementary schools in the northern part of District 3—a district that includes a portion of Harlem in addition to the Upper West Side—now have fewer than 300 children; three have fewer than 200. And, because the children who stay tend to be needier than those who leave, the traditional zoned schools have higher concentrations of poverty and more children with special needs than they would have if everyone who lives in the neighborhood attended their zoned neighborhood school.

While the schools in the southern part of District 3, serving more middle class children – including those from Harlem – have grown in popularity, many in the northern part of the district struggle to fill their seats. Just 37 percent of the public school pupils who live in the northern part of District 3—the area north of Central Park, south of 124th Street, east of Morningside Park, and west of Fifth Avenue—attend one of the seven zoned neighborhood schools, according to a preliminary analysis of students’ zone assignments for the 2015-16 school year by the Center for New York City Affairs. Nearly as many, 36 percent, attend charter schools (including five that share space with zoned schools in the area); and 27 percent attend other public schools, including gifted programs and other school of choice. In all, the 2447 elementary school age children who live in this small area attend an astonishing 176 public and charter schools—and this analysis does not include children who attend private or parochial schools.

This dynamic is repeated in other communities where parents, apparently dissatisfied with their neighborhood schools, exercise school choice to find other spots for their children. Citywide, about 60 percent of children attend their zoned neighborhood schools, according to the Center’s analysis; in Brooklyn’s District 16 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, however, just 24 percent do; in District 17 in Crown Heights, 30 percent do; in District 13 in Fort Greene, 34 percent do.

Charter schools have proliferated in Harlem in the past decade, both in District 3 and in neighboring District 5. But even before the charter schools opened, parents had long taken advantage of the city’s extensive system of school choice to exit from their zoned schools. Alternative public schools, such as Central Park East in East Harlem and Manhattan School for Children on the Upper West Side, admit children by lottery. Gifted programs, such as one at PS 166 on the Upper West Side, admit children according to results on standardized tests.

City Department of Education (DOE) officials, school leaders, and some parents agree the status quo of too many schools with too small enrollments is not sustainable. They assume that not all the schools will survive, at least in their current form; some may need to merge. The DOE threatened last year to close as not financially viable one school, PS 241, which then had an anemic enrollment of only 112 kids. The District 3 Community Education Council (CEC), the elected panel of parents charged with drawing up zoning lines, won a reprieve for the school, where enrollment has risen to 132 students this year; whether enrollment can rebound to healthier levels is, however, an open question.

Kim Watkins, a member of the CEC, says that the glut of 13 traditional and charter schools packed into a small area makes engineering turnarounds a steep challenge. “This sets up schools to compete for resources with one another,” she said. “It splinters the community,” diffusing the parental involvement that’s key to making successful elementary schools click.

In response, Watkins spearheaded a Harlem Parents Summit last Saturday at PS 242 (enrollment: 184 students). Some 150 parents and educators from local charter and traditional elementary schools took part in a frank assessment of the current lay of the land and a discussion on forging a more hopeful “shared agenda for Harlem schools.”

The intent of the summit – rebuilding community trust and commitment – is crucial to reviving any beleaguered school. And a heartening example of such a turnaround is close at hand. Just a few blocks outside District 3 in District 5 involved parents have helped PS 125, once an under-enrolled school avoided by local parents, flourish and grow; it’s now a robust place with a waiting list for kindergarten. What Watkins and others hope is that some schools in District 3 can make similar gains.

Clara Hemphill is director of education policy at the Center for New York City Affairs. The research data and graphics for this week’s Urban Matters were developed by Ana Carla Sant’anna Costa, education policy research analyst at the Center.