January 15, 2020

Love and Death on the Streets of New York: Why West Side Story Is Back

Explosive and genre-busting when it premiered more than 60 years ago, West Side Story has, in more recent years, often come to be seen as a significant but perhaps dated artefact of 1950s popular culture.

But that may be about to change. A radically new production of West Side Story will open on Broadway next month. And a new West Side Story movie, directed by Steven Spielberg and using locations in Harlem and Paterson, NJ, is to come to the screen later this year.

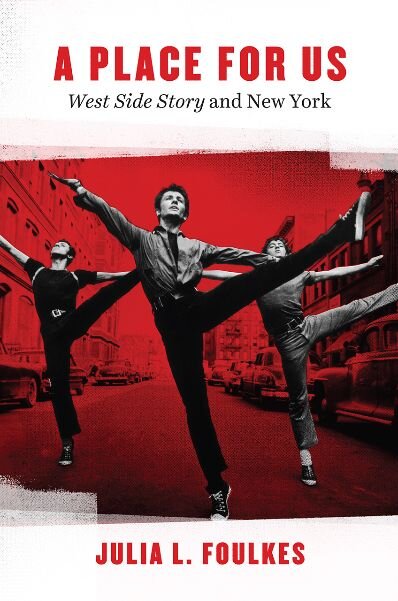

We asked Julia Foulkes, a professor of history at The New School and author of the acclaimed A Place for Us: West Side Story and New York, about the new life and enduring meaning of this musical theater classic.

Urban Matters: Why this big revival of interest in West Side Story now? Do you see something in this moment that gives it new relevance?

Julia Foulkes: Even though I have spent years thinking about this show, I think it is odd that such attention is being paid to it right now! There may be a certain amount of nostalgia in looking back to this classic production—to a New York of gang fights with knives rather than driven by drugs and guns, for example—but I think there are also key themes that resonate today, primarily the one of belonging, what we now might call the right to the city. Who gets to claim a space in New York, a place for themselves? Who has the right to walk down a block, any block? In the original production the migration of Puerto Ricans into New York made a classic Shakespeare tale come alive in new ways, highlighting the role of discrimination and prejudice in shaping the answer to who belongs in this city. Unfortunately, that question is still too relevant, heightened by ideological and political differences about migration and inequality. What West Side Story presents is the life-and-death consequences that are at stake: the joyous, wondrous hope of love and the tragic, deathly outcomes of hate—all played out on the streets of New York.

UM: In A Place for Us, you write, “Musicals don’t change the world, but they do shape how we see it.” How do you think West Side Story has shaped how the world sees New York City?

Foulkes: Skyscraper-high aspirations—if you make it here, you can make it anywhere—govern most visions of NYC in films, songs, TV shows, advertisements. One of the reasons that I think WSS has spread around the world and across decades is that it burnished that image to one that recognized limitations—of the city, the U.S., people. Yes, you might find your spot on a block in this ambition-driven city but you’re going to have to fight for it, and there will likely be unexpected and possibly tragic consequences. A lot of musicals have presented fairytale images of New York; the genre lives on the fantasy of people singing and dancing their emotions and lives. What I think WSS does is show the battle for the fairytale without giving up on it altogether.

UM: West Side Story has elements tied to a particular time and place, as well as basic themes relevant since Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. How can a modern production breathe new life into this story?

Foulkes: What WSS changed from Romeo and Juliet is shifting the feuding families of Verona to street gangs, and the friar’s well-intentioned if mismanaged communication to outright discrimination against the messenger Anita. Gangs are families of a kind but primarily for young people. That youth-focused world does make WSS more modern. I think the near-rape of Anita is one of the parts of the WSS that may be even more relevant today. Its violence still shocks and perhaps redounds more acutely because of the recent highly publicized acts of sexual discrimination and abuse against women.

But I do think that young people in New York today face different challenges. I think for WSS to matter, beyond being a period piece, it has to reflect the constant turmoil that shapes our lives here, now. Economic inequalities are far more extreme today than in the 1950s, and Manhattan is not as dominant in the vision of New York as it once was. Those physical and demographic changes might infuse a re-imagined current-day WSS placed in Jamaica, Queens or the South Bronx with young people trying to pay rent, find jobs, love and live boldly, in a wildly inequitable city.

UM: Jerome Robbins’s choreography was the heart of the original West Side Story, and Robbins was arguably the prime force in creating the play. The new Broadway production doesn’t use his choreography. You’re a major Robbins scholar: Can there be a West Side Story without the dances he created?

Foulkes: Of course! In fact, I’m delighted that the Robbins Foundation has allowed changes in choreography in [the new production and new movie], which they have not permitted before. Robbins gave dance a central role because he knew that it could best convey the tension, drama, and joy of the story—finding your place meant taking up space in the city. Dance embodied that claim directly. New choreography only makes that more likely to happen now because the way we move, why we move has changed. Dancing on the street—breakdancing, hip-hop, on street corners, in the subways—all became common after the 1950s! I think new choreography can reflect a more contemporary sensibility to movement in the city, with dance as a more common and informal means of making our way. But I am interested in the fact that no one seems willing to change the music! Perhaps a new score would change our perceptions of the story most radically.

UM: Final question: You’ve seen the new Broadway production in previews. Does it achieve director Ivo van Hove’s goal of “making a West Side Story for the 21st century?” Or will West Side Story always work better as a time capsule from an earlier New York?

Foulkes: I saw a very early preview and I understand that changes are ongoing until its opening so it’s hard for me to give a definitive answer. There are some choices that reflect current-day ways of being in the city, although maybe not enough in the version I saw. I will say that I think audience members bring many competing ideas of WSS to any revival of it. Perhaps they were in a high school production, saw the movie as a commentary on Romeo and Juliet, know parodies of it rather than the original, or heard various songs in improvisational jazz renditions or on a talent show. WSS has not remained static, even if there is a script, a score, etc., and we bring many snippets, memories, family lore about it with us to the theater. An “authentic” version is probably not a reasonable or even reachable goal. Because of that I favor boldness in the re-imagining—shaking off expectations, maybe even twisting or banishing long-held iconic motifs—and delivering a new story for a new age.