Better Child Care, For Fewer Children?

BY ALEC HAMILTON

February 8, 2012 — A city program that pays for child care and Head Start services for low-income children is about to be redesigned in a way that may result in higher quality services — but for far fewer children.

In 2011, total enrollment in city-subsidized child care programs was about 117,000. Through the Administration for Children's Services (ACS), the city supports child care programs for the city's lowest-income children at nonprofit centers and Head Start programs, as well as in private homes. Last year, the agency announced a planto revamp requirements for its service providers, in order to make early education and developmental screening available to all kids in city-funded child care.

While children's advocates praise the city's efforts to ensure high quality care, many worry that the changes will lead to a substantial reduction in capacity — especially because the new programs will be more expensive for providers to run. Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg's proposed Executive Budget released last week, the city would fund care for 8,200 fewer children in the coming fiscal year, according to ACS.

Nancy Kolben, executive director for the Center for Children's Initiatives, calls the plan "a step forward in the city's vision for early child care." However, she says, "given the shortfall in funding, it represents a step backwards in terms of the ability to serve the same number of children and allow programs to meet the higher quality standards."

The Bloomberg administration has reduced the number of children it supports in subsidized child care over the years: In 2007, enrollment in city-subsidized child care was about 127,000, according to mayor's office documents. Today, that number is about 10,000 less.

Last year, the mayor initially proposed cutting an additional 7,000 slots at child care programs that contract with the city, but he and the City Council ultimately restored most of these in the final budget they enacted last June. Even if the Council again restores funding at last year's level, it will pay for several thousand fewer slots under the new program requirements, say advocates.

The new ACS initiative — known as EarlyLearn NYC — calls on programs to institute higher teacher-child ratios, bring social workers into the classrooms, combine subsidized-care children with kids whose families pay privately, and provide more support for families. ACS anticipates it will fund approximately 350 contracts, totaling approximately $515 million annually.

The city is targeting the largest share of funding to zip code areas with the greatest number of children in poverty. While the intent is to concentrate services where they are most needed, advocates say there will be consequences, including less funds for child care programs that operate in or near housing projects in otherwise higher-income neighborhoods, such as the Upper West Side. Amy Cohen, director of government contracts at the Jewish Child Care Association, predicts many low-income children outside of the designated areas will be left without services.

"There are a lot of kids living in pockets of poverty in New York who are going to be eligible but are going to lose their care," says Cohen.

The city estimates there are nearly 290,000 New York City children eligible for subsidized child care. The funding for center-based child care should cover about 34,700 of those kids, with nearly 96 percent of that funding reserved for centers in targeted high-poverty neighborhoods. The plan from ACS is less specific about the distribution of slots for home-based child care programs, but says contracts will be awarded with a similar emphasis toward targeted areas.

While government funding currently covers the entire cost-per-child enrolled in the programs, next year's contracts will require providers to cover a small percentage of the total cost by using tuition from children whose families pay privately, or use charitable donations and volunteer hours.

"It's doing more with less, but in excess," says Cohen.

Providers will also become responsible for health insurance for their employees, who are currently covered through the city's central insurance plan. Most employees at these agencies are protected by union contracts which mandate that employers provide coverage.

While child care centers run by the city's largest nonprofits may be able to fill in funding gaps with grant funds, Liz Accles, a senior policy analyst at the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies, worries that the new system will place smaller community-based organizations at a distinct disadvantage.

Accles says that rushing into a citywide rollout of the new program without addressing these concerns may be premature. "Now is certainly not the time to be doing it in full-force" she warns. "We should be able to test a model and test costs and troubleshoot on a manageable scale. Many elements are good, but without adequate funding it's just not going to be possible to reach the vision that the city is imagining. "

ACS acknowledges that the new program structure may require changes, "such as the number of classrooms per site and children per classroom," writes spokesperson Tia Waddy in an email. But she says that the proposed rates will adequately fund contractors to operate high quality programs. "New York City's commitment to providing quality child care is based on the strongly held belief that success in school and in life is positively linked with the experience of quality child care. ACS, like many other city agencies, is operating under severe financial constraints, but we have never wavered in our belief that providing quality child care is one of our top priorities."

Budget negotiations will go on through April. Advocates are calling for the mayor and City Council to fully restore funding for the programs.

News Brief: Could Plan to Speed Adoptions Have Unintended Consequences?

BY KENDRA HURLEY

January 26, 2012 — The Administration for Children's Services' (ACS) recently releasedstrategic plan places a heavy emphasis on speeding up the pace at which young people move out of foster care and into permanent homes. But some attorneys and parent advocates are urging caution, worried that proposed new financial incentives tied to federal adoption timelines could have unintended results.

There's no denying that many New York City kids are spending a very long time in foster care. More than one-third of New York City foster children aged 18 and younger have spent at least three years in foster homes, according to city data. That's better than it used to be: Today, half of the children entering care for the first time are back home within six months, down from 11 months in 2007.

Nonetheless, those on the adoption track still wait more than four years, on average, before leaving foster care. The long length of stay for would-be adoptees has hardly budged in recent years even as the size of the foster care system has shrunk. "Children are growing up without families, and there's nothing more devastating I could imagine than for a child to grow up without a family," says Marcia Lowry, executive director of Children's Rights.

The new ACS plan includes popular ideas to deal with these long lengths of stay, such as streamlining practices in the city's notoriously slow and backlogged Family Court. But Bloomberg administration officials have proposed another strategy that is proving controversial: giving foster care agencies financial incentives to meet a timeline set by the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA).

ASFA, the sweeping 1997 federal law that attempted to cut lengths of stay in foster care, requires that agencies seek to terminate parental rights as soon as a child has been in foster care for 15 out of any 22 month period. But as of last summer, officials say, more than 95 percent of the approximately 3,300 New York City children who reached 18 months in foster care that year had not been the subject of a Family Court petition to free them for adoption.

"Federal timeframes and New York State statute must serve as guidance in our practice with children in foster care," says ACS Commissioner Ron Richter. "Children's timeframes are different than an adult's, and we have an obligation to achieve timely permanency planning for children in our care. Our foster care agency partners must make efforts to reunify families where possible, and when reunification isn't possible, another plan must be obtained."

Parents' rights advocates contend that financial incentives would have the opposite effect of what the city intends. Nonprofit agencies that run the foster care system for the city are paid a per diem rate for each day a child spends in foster care—and adoptions generally take much longer to complete than reunifications. This means there's a built-in incentive for foster care agencies to favor adoption, explains Mike Arsham, executive director of theChild Welfare Organizing Project, a parent advocacy organization.

"Setting a goal of adoption is going to drive up the average length of stay," says Arsham. "If you can set a goal of adoption for a significant number of children in your care, then you can ensure a cash flow."

Many children spend longer periods in foster care while their parents try to kick an addiction, finish a prison sentence or complete programs required to prove they're ready and able to safely care for their children. "Say a person has a drug problem and goes into drug treatment, and they have a couple of relapses before they are able to retain sobriety, and it takes two years rather than 19 months," says Chris Gottlieb, an attorney with New York University's Family Defense Clinic. "To speed that case to adoption doesn't serve the best interest of the child." In such a case, she adds, "it would not be appropriate to file a termination of parental rights."

Eric Nicklas, chief operating officer at the foster care agency Forestdale, Inc., says that because the foster care system has shrunk in size, a higher portion of its families present difficult challenges that take longer to resolve. "If you have a system that works to keep kids out of care, then the ones that are left are the ones for whom there is no easy solution. This is how it should be," says Nicklas, who worked at ACS for more than 10 years in its office of research evaluation and its foster care division. "But there needs to be a recognition that it takes more investment to get the kind of outcomes for these families we all want."

Nicklas says there's a danger in putting incentives only on adoption milestones, adding that ACS should keep financial incentives on actual permanency outcomes, including when a child is returned home.

Many of the city's 14,000 foster children are already exempt from ASFA's timeline, including the nearly 35 percent who live with relatives, whose homes are considered stable placements. Others, including some children with parents in prison or drug treatment programs, have been exempted.

"There's such a huge percentage of those kids there at 18 months who should go home," says Gottlieb. "It'd be much better to focus on the ones who have been in care three years and four years. Those are the ones who won't come home. And then let's talk about why they're not [moving out of foster care] more quickly."

Sandra Killet, a parent advocate at the foster care agency Children's Village, says that terminations of parental rights can have dire consequences for teenagers who end up as "legal orphans" because they have been legally separated from their parents but never adopted. Today, there are more than 550 young people in New York City who are neither legally tied to their parents nor living with a family who plans to adopt them. "Should we really be doing this? Is this in the best interest of the child?" asks Killet.

But others point to the long periods of time infants and toddlers spend in foster care—months that can add up to the better part of their short lives.

"For kids in foster care, every month matters. You only get to be 5 years old or 8 years old or 10 years old once," says Jim Purcell, chief executive officer of the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies. "I want to see our agencies, ACS, and the courts bring a greater urgency to the decision-making so things move along, but I'm not necessarily in favor of rigid timeframes that might not work for some of our families."

" We will work collaboratively with our foster care agencies to develop strategies that will help us meet ASFA timelines, with an awareness that one-size-fits-all is never an appropriate approach," adds Richter. "Each family's challenges are different and each child's needs and interests their own."

News Brief: Governor decides—in juvenile justice, city kids belong near home

BY ABIGAIL KRAMER

January 17, 2012 — If Governor Cuomo gets his way, New York City will cut the number of children it sends to state-run juvenile justice facilities by more than two-thirds over the next two years, receiving more than $35 million per year from the state to create a new spectrum of services and incarceration facilities for juvenile delinquents within the five boroughs.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg first called for the creation of a comprehensive, city-run juvenile justice system more than a year ago, citing an 81 percent recidivism rate at the state's juvenile prisons and the bloated costs to city taxpayers of supporting an inefficient statewide system. Until today, neither city nor state officials have been willing to provide public details on the progress of the plan, but the two administrations have been in negotiations for the past several months, agreeing on logistics and a financing structure shortly in advance of the governor's executive budget proposal, released earlier today.

"Too many of our young men are sent to prison and lost to the system," the mayor said today. "The governor has proposed a sweeping, progressive reform that will transfer primary responsibility for all but the most seriously delinquent youth from the state to the city, allowing our young people to remain closer to their families and receive the individualized services, supports and opportunities they need."

If the governor's "Juvenile Justice Services Close to Home Initiative" is approved by the state legislature, New York City will take jurisdiction of children who are currently confined in the state's so-called "non-secure" and "limited secure" facilities—a total of 324 kids. Young people who are determined by Family Court judges to require high-security facilities, which look and operate much like adult prisons, will remain in the charge of the state.

It is unclear whether the new programs will also apply to young people currently placed in nonprofit-run residential treatment programs outside the city.

The city does not plan to directly operate any of the planned new facilities. They will instead be developed and run by nonprofit organizations under contract with the Administration for Children's Services, according to a source familiar with the plan.

In the first year of operation, the city would be eligible for a block grant of $35.2 million in state funds for its new services. The grant would go up the following year to $41.4 million and be subject to annual appropriations thereafter. Once the state approves the city's plan, it would also be authorized to shut down facilities of its own—a move that has traditionally been fought by guard unions and many upstate legislators. Governor Cuomo estimates that the measure would cost the state $3 million next fiscal year (which begins in June of 2012), but result in a net savings of $4.4 million when fully implemented in 2014. It's still unclear how much money the city would save under the plan—but if state facilities are closed, the city would likely see significant savings in its own budget.

Advocates for juvenile justice reform in New York City have long called for kids to be housed and served closer to home. "It cannot be understated how important it is for youth who have to be in juvenile justice placements to be placed close to their homes, schools, communities and lawyers," says Stephanie Gendell, associate executive director of the Citizen's Committee for Children.

But while the plan creates new possibilities for young people to remain close to their families and support systems, it leaves many unanswered questions about how an expanded city-run juvenile justice system would operate:

Will the city fund new lockups for kids? Who will run them and how?

The state currently operates five juvenile justice facilities inside New York City. Under Cuomo's proposal, the city would be authorized to lease those facilities for one dollar a year. The city is likely to lease three of the five and turn them over to nonprofit organizations, according to a source familiar with the negotiations. Since there are no city-administered detention programs that qualify as "limited secure," it is unclear which organizations would be qualified to provide a level of confinement and services consistent with those currently offered by the state.

Jeffrey Butts, a justice scholar at John Jay College who has worked with the city on analyzing its juvenile capacity needs, notes that a city-administered system could create new financial incentives to keep kids out of lockups altogether, since incarceration is many times more expensive than alternative programs that provide community-based supervision alongside services like family counseling and job training. "If you have $100 to spend and you can either use that money to put one kid in a facility or work with three or four kids in the community, you'll find that the impulse to put kids in secure facilities goes way down," says Butts.

Over the past several years, the city has created a spectrum of such alternative programs, decreasing the number of kids it sends to state lockups by more than two-thirds since 2000.

Governor Cuomo's plan does not require the city to reinvest the money it may save from reduced state incarceration into community programs for kids in the city's new system, or into building high-quality residential facilities for those kids who will continue to be locked up. Some advocates for juvenile justice reform worry that financial pressure may work against the interests of young people who end up in city-run residential programs.

"Children who are incarcerated should be placed only in very small facilities staffed by well-trained employees familiar with children's developmental needs and committed to helping them succeed," says Gabrielle Prisco, director of the Juvenile Justice Project at the Correctional Association. "Incarcerated children should receive the kinds of meaningful treatment services shown to both help them improve their lives and decrease recidivism."

Prisco's vision echoes the model that's been described by several of the city officials most deeply involved in juvenile justice reform efforts, but so far there's been no commitment to spend the kind of money that such a system would require. What these advocates say they don't want to see is high-volume, service-poor facilities, regardless of whether they are administered by the city rather than the state.

How will a city system avoid the abuses that have plagued the state's juvenile facilities?

Juvenile justice reforms at both the city and the state level were spurred, in large part, by revelations of widespread abuses in state facilities, including a federal investigation that found rampant overuse of physical force in four state-run lockups.

New York City has its own spotty record on juvenile incarceration. The city currently operates two secure detention centers for children awaiting hearings in Family Court or transfers to state facilities. According to the city's most recent quarterly incident report, young people in those facilities were injured by guards 55 times between July and September of 2011—an average of more than once every other day.

While the city has taken steps to improve conditions in its detention facilities (most notablyclosing the infamous Bridges Juvenile Center, which had been marked by decades of scandal and abuse), the bulk of its reform efforts have been directed at diverting kids to community programs. State facilities, in the meantime, have introduced a therapeutic discipline model and standards for the use of physical force and restraints aimed at reducing injuries to young people in its care.

Jeffrey Butts of John Jay College notes that detention centers are an imperfect parallel to longer-term incarceration facilities, since their conditions are inherently more volatile. "You have quick turnarounds and high-stress circumstances with kids who aren't sure what's going to happen to them," he says. "There are bound to be more incidents."

While the city programs would be run by nonprofits, advocates worry that any improvements may not survive into future administrations. "Although both the city and state have recently engaged in important reforms, any transfer of power must be predicated on more than the successes of current administrations," says Prisco of the Correctional Association. "Administrations inevitably change and it is imperative that a strong and durable system of protections for children be built into the legal framework of any youth justice system."

Who will regulate, oversee and monitor the city's expanded juvenile justice programs?

Under Cuomo's proposed legislation, New York City's plan for new facilities and services must be approved by the Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS) before it can take effect. OCFS, which operates the state's juvenile justice system and regulates the city's foster care system, will have ongoing oversight and monitoring responsibilities for the city's expanded juvenile justice services, along with the power to retract funding.

As a function of the mayoral administration, the system would also presumably fall under the oversight powers of the City Council and the city Comptroller.

As part of its proposal for providing the new services, the city would be required to hold a public hearing on its plan and justify reasons for disregarding any significant commentary. Still, some juvenile justice advocates question the city's likelihood of incorporating meaningful community input into the design or operation of its new services—particularly, they maintain, since the city excluded them from its planning and negotiations with the state.

"There are a lot of people in the community who are very excited about this," says Avery Irons, director of youth justice programs at the Children's Defense Fund of New York. "We want kids close to home. If the city puts together a plan that we can support we'll stand with them the whole way. They might be surprised at the levels of support and offers of assistance they'd get from community agencies. But we need that plan. They have to open up enough to hear our voices."

One Step Back: The delayed dream of community partnerships

BY ABIGAIL KRAMER, KENDRA HURLEY AND ANDREW WHITE

Nearly five years ago, New York City's Administration for Children's Services launched a plan to create a culture of community participation and transparency in the child welfare system, which is responsible for protecting children and assisting families in crisis. Its Community Partnership Initiative sought to establish neighborhood collaboratives with organizations and residents in 11 districts that have high reporting rates of suspected abuse and neglect.

Not only would the system become more accountable and connected, but children would be safer, with communities taking part in the work of child welfare, helping to identify families on the edge of crisis, and preventing them from tipping over. Today, the partnerships train community representatives to help parents navigate the child welfare system. They forge relationships between child care providers, who encounter families every day, and preventive service agencies who can help stabilize families if they run into trouble. They have created opportunities for child protective services officials to meet with local people, share neighborhood data, and discuss what it means for government and communities to try to keep children safe.

But the initiative's original aspirations were much greater. This edition of Child Welfare Watch looks at the progress of the city's community partnerships—at their accomplishments as well as their very real limitations, and at the vision they still represent for a child welfare system that answers to the communities it's designed to serve. Our findings include:

- While partnerships provide valuable assistance to a small number of families with children in foster care, their work remains largely on the margins of the system. They have not received the investment or support they would need to achieve broad-scale change.

- In 2008, the city planned to double the funding for each community partnerships and to expand their reach. That plan never materialized. Total funding distributed to partnerships has remained static at $1.65 million—barely more than .1 percent of child welfare spending in New York City. (See "No Easy Choices.")

- In 2010, ACS held 9,235 child safety conferences, allowing parents to meet with the workers who decided whether their children should be placed in foster care. Community partnerships sent representatives to 1,395 (15 percent) of these conferences, with the goal of helping parents participate in decisions about their families. (See "Shifting the Power Dynamic.")

- Each partnership is responsible for facilitating 40 visits per year, where kids in foster care can spend time in the community with their parents. Many of the partnerships' visiting services have been underutilized due to a lack of referrals from foster care agencies. (See "The Tricky Thing About Visits.")

- Foster care in New York City costs 42 percent less than in 2000, but the city has not stuck to its plan of reinvesting savings into services that help stabilize struggling families: Adjusted for inflation, city taxpayers spend almost the same on preventive services as they did 12 years ago. (Download the report PDF to read "The Dream of Reinvestment.")

This report looks closely at two of the partnerships' most promising projects: their work in child safety conferences, where they amplify parents' input in identifying services and resources that might help their families; and their role in improving parents' visits with children in foster care which can speed up reunification. The report also looks at the larger context of the city's commitment to prevention, strengthening the power of communities to keep children safe at home.

The report offers a set of policy recommendations informed by the research and drafted by a panel of practitioners, experts, parents, young people and others, aimed at helping policymakers better support partnerships to do meaningful work. These include:

- ACS and City Hall should commit to—and invest in—resources and supervision that will enable partnerships to produce impressive results.

- ACS should begin tracking outcomes data that demonstrate the partnerships' impact on family support and stability.

- The ACS Office of Community Partnerships should provide more skilled expertise, guidance and facilitation.

- ACS should hold foster care agencies accountable for participating meaningfully in community partnerships.

- Partnerships should recruit community residents with experience of the child welfare system.

- New York City Family Court should create designated court parts for neighborhoods with well-developed community partnerships.

- Community partnerships must have room to develop their own agendas and pursue goals that strengthen and expand neighborhood resources.

Special audio feature:

Listen to "community reps" from the Child Welfare Organizing Project talk about their work helping parents in crisis, as ACS workers decide whether or not to remove their children.

News Brief: Mayor's Axe to After-School?

BY ALEC HAMILTON

December 12, 2011—The Bloomberg administration is poised to make sharp cuts to the primary source of government funding for hundreds of free after-school programs that currently serve about 53,000 children across the city.

Just two years ago, the city's "Out-of-School Time" or OST program received more than $117 million in city funds and served more than 87,000 kids. This fiscal year, the program was reduced to $90 million in city dollars. And now, a recent contract proposal from the administration indicates that, in 2013, the program will be cut to just under $70 million. Advocates say the reduction will nearly halve the number of program slots available to city kids.

"The proposed decrease is just going to be devastating to the system at a time when there is such a high demand," said Kathleen Fitzgibbon, senior policy analyst at the Federation for Protestant Welfare Agencies, which represents 20 of the more than 400 community agencies that currently run the after-school programs. The cuts would be hard not only on the children shut out, she said, but for their families, who rely on the programs for childcare.

"What are working parents going to do?" she asked. "Will they lose their jobs?"

Fitzgibbon said she is also concerned about the jobs lost to providers. "Since 2009 we've seen the loss of five thousand jobs as a result of cuts."

Cathleen Collins, deputy chief of staff at the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), which distributes funding for the program, said in an email that one reason for the anticipated cut in slots is that the cost per child is expected to increase.

"In the new RFP, all programs will be required to provide services both during the school year and over the summer. The average price per participant for services is therefore expected to be higher than in the past. In addition, the new RFP sets out a rigorous program model with a strong focus on academics, including the requirement of an education specialist in every program. In recognition of the cost of high-quality services that will yield the positive outcomes we want for our young people, DYCD has increased the maximum price per participant that providers can propose, which necessarily reduces the number of participants that may be served."

Collins said it is too soon to know how many kids would lose services as a result of the funding cuts, as the number of program slots will depend on the proposals that the city receives. She also cautioned that there "are still some budgetary issues at play."

Norah Yahya, a policy analyst for United Neighborhood Houses of New York, maintained that the current situation is different from the usual back-and-forth that organizations engage in with the mayor at budget time. "It's dire," she said. "Cuts of this magnitude to services are not usual."

Programs supported by OST after-school funding are free, and offer academic support, cultural activities and healthy snacks for children after school hours and during school holidays and summer. When the contracts were restructured in 2005, Mayor Bloomberg described the program as a "long overdue" means of providing supervision and enrichment to kids who have nowhere else to go after 3pm. "Our new Out-of-School Time system will better serve children and working parents by engaging youth at precisely the times of the day when they are likely to be home alone or are most vulnerable," he said.

Vickie Lopez is a medical secretary at New York Hospital whose two daughters, ages five and seven, had been attending a city-funded after-school program since they began kindergarten. Last year, program reductions meant they were no longer able to get spots, she said. "I cried," Lopez remembered. She was placed on a waiting list, but said she never heard anything more.

Finally a friend of a friend offered to watch the girls for $150 a week, three hours a day. "It was a very, very rough year for me," said Lopez. She said at times she was forced to bring one of her kids to work with her out of desperation.

A 2011 report by Policy Studies Associates analyzing 10 after-school providers funded by the program found that 84 percent of youth enrolled were black or Latino, nearly one-quarter were English Language Learners, and 18 percent were special education students.

Contracts for the revamped program are due to start in September of 2012 and will last three years. They are funded almost exclusively with city tax revenue, with a small amount coming from the state.

The after-school cuts come at the same time as proposed steep reductions in the availability of government-funded childcare slots for preschool-aged kids, following the loss of federal funds for those programs. They also come just four months after Mayor Bloomberg announced the launch of the Young Men's Initiative, billed as an effort to reduce "the broad disparities slowing the advancement of black and Latino young men." Over three years, the mayor has committed a public-private partnership to creating more than $127 million in programs to "connect young men to educational, employment, and mentoring opportunities."

Yahya said the after-school programs are particularly important for low-income black and Latino youth. "This isn't just a babysitting club." In addition, she said, many of the programs make a point of hiring people from the communities they serve, which allows kids to have a mentor who understands where they are from. "The children can see themselves in their mentors, in working adults that care about them and are successful."

"I'm fearful for what the future holds for youth services, as the pot for them gets smaller and smaller," she added. (The city cut DYCD's total budget by close to $40 million this year.) Programs, said Yahya, are now so stripped down that new cuts likely cannot be absorbed through reductions in supplemental services. "A lot of specialties have already been eliminated. They're down to the marrow."

News Brief: Council Says Raise the Age...Sort Of

BY ABIGAIL KRAMER WITH ADDITIONAL REPORTING BY ALEC HAMILTON

November 30, 2011 —The City Council passed aresolution Tuesday urging the state legislature and Governor Cuomo to send 16- and 17-year-olds accused of nonviolent crimes through the juvenile justice system, rather than automatically prosecuting them as adults.

The resolution supports a proposal made in September by New York's chief judge, Jonathan Lippman. Lippman's proposal would re-route adolescents accused of "less serious offenses" through family courts, where they have access to services and programs not available to those tried as adults. The proposal follows a decade-long national trend toward removing adolescents from adult courts, jails and prisons. New York and North Carolina are the only states that still automatically try 16-year-olds as adults. Eleven states set the age of criminal responsibility at 17 while 37 states and the District of Columbia set it at age 18.

Even if New York adopts the changes urged by the City Council, the state's policy would remain among the most stringent in the country. The law would continue to send children to adult courts and prisons if they are charged with violent crimes. Only 23 other states do this, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The majority of states mandate that children first be adjudicated in the juvenile justice system, where judges have the discretion to transfer them to adult court if they believe that circumstances warrant a criminal prosecution.

Last year, more than 42,000 young people aged 16 and 17 were prosecuted as adults in New York State, according to the Division of Criminal Justice Services. Of those, 74 percent (31,764) were charged with misdemeanors; 12 percent (5,341) were charged with nonviolent felonies; and 13 percent (5,727) were charged with violent felonies.

Another 598 children under the age of 16 were tried as adults last year under the state's "juvenile offender" law, which sends children as young as 13 to adult court if they are accused of certain serious felonies. Of those, 77 percent were charged with robbery; 13 percent with assault; three percent with a weapons charge; one percent with homicide. Even if convicted, these juvenile offenders are not incarcerated with adults until they are at least 18 years old.

Judge Lippman has not provided full details on which crimes he wants to see shifted to juvenile courts. "Those juveniles who commit...serious offenses can and should be prosecuted in criminal court," he said in a speech to the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City in September.

Others in the court system disagree. "It's the age of the person more than the offense that we should be looking at," says Judge Lee Elkins, who has presided in the Kings County Family Court since 1995. "The whole issue is driven by knowledge about teenagers' development, and the reality that teenage brains are not fully developed in terms of executive function. I don't think that the offense alone should be the determining factor" in deciding where adolescents are tried, he says.

Elkins also maintains that the proposed changes must be considered within the realities of New York's notoriously overburdened Family Court system. "My concern is that we be adequately resourced," he says. "With the budget cuts, everyone is already doing their utmost with less. Please don't impose additional burdens on us without providing additional resources."

Bloomberg administration officials declined to comment on whether they have begun to assess the logistical and financial challenges of expanding the Family Court, juvenile probation and detention systems, but a Department of Probation spokesperson said "This is something we're interested in and we're looking into it."

In September, John Feinblatt, chief policy advisor to the mayor, told The New York Times, "The practical considerations should not shut down the discussion...They should be part of the discussion."

In a City Council hearing earlier this month, several advocates for low-income youth testified that the proposal should include children charged with more serious offenses.

Research on adolescent brain development, for example, which Judge Lippman cited in his September speech and in testimony to the City Council, "does not make a distinction between nonviolent and violent adolescent acts," said Gabrielle Prisco, director of the Juvenile Justice Project at the Correctional Association of New York, a watchdog group with the authority to inspect and report on state jails and prisons. "We do not...say that some children have demonstrated through their actions an adult-like tendency, and so should be able to serve in the military, vote, or enter into a contract with AT&T."

Both Judge Lippman and the City Council have cited data indicating that adolescents who leave the juvenile justice system are significantly less likely to commit another crime than those who spend time in adult jails and prisons. In 2006, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed six studies that compared recidivism rates between young people who had committed similar offenses but been sentenced through the different systems. Four of the six concluded that processing young people through juvenile systems decreased recidivism by a median of 34 percent.

That data is not limited to nonviolent offenses. In fact, one of the studies in the CDC analysis compared young people charged with comparable, serious crimes in New Jersey, where they were treated as juveniles, and New York, where they were prosecuted as adults. The New York youth were 39 percent more likely to be re-arrested on a violent offense than their juvenile peers across the state line.

Councilmember Sara Gonzalez, who chairs the Council's Committee on Juvenile Justice and was the lead sponsor of the resolution declined to comment on the Council's decision to restrict it's resolution to adolescents accused of nonviolent crimes.

In a cost-benefit analysis commissioned by the legislature of North Carolina, which is considering a bill similar to the one proposed by Judge Lippman, The Vera Institute of Justice found that routing 16- and 17-year-olds accused of nonviolent crimes through that state's juvenile justice system would save taxpayers a significant amount of money over the long-term. The policy change was projected to cost the state $49.2 million in additional spending per year. But the authors estimated it would also generate $123.1 million in benefits to young people, victims and taxpayers for every year that young people were routed through the juvenile justice system. Much of that benefit was predicted to come from lower recidivism rates and from freeing young people from the long-term consequences of a criminal record on employment.

The Reinvestment Myth: Beyond the IBO Report

BY ANDREW WHITE

October 20, 2011—The idea of reinvesting savings from one part of the child welfare system into another sounded perfectly logical when it was first proposed in a city strategy paper in 2001—especially to anyone unfamiliar with the vagaries of government social services funding.

More than a decade ago, before Michael Bloomberg became mayor, New York City policymakers saw a huge trend in the making: the number of children in foster care was tumbling downward, alongside crime rates and the once epidemic use of crack cocaine. Of course, there were other factors: families were helped by great improvements in the city's economy, for example, and there was also a growing realization in the child welfare field that placing 10,000 or more children in foster care each year was no panacea for what ails troubled families living in severe poverty.

So in 2001, the Administration for Children's Services (ACS) established a reform goal of reinvesting savings from the shrinking foster care system into social services, including case management, drug treatment, counseling, benefits advocacy, homemaking and more—all designed to help families, keep children safe and prevent placements in foster care.

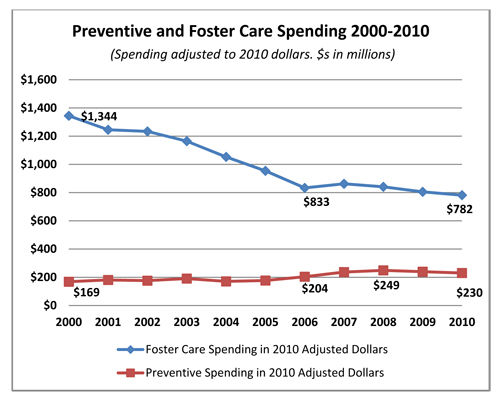

Did it happen? Not so much. The charts below show there was very little reinvestment despite a huge, 40 percent decline in overall government spending on New York City foster care between 2000 and 2010. Remarkably, the number of foster children continues to fall. As of July 2011 there were 14,308 foster children, down 58 percent since 2000.

And yet, this year, New York City taxpayers' contribution to preventive family support services is almost exactly the same as it was 12 years ago.

With the help of the NYC Independent Budget Office (IBO), Child Welfare Watch mapped the impact of the last dozen years in budget and spending trends on ACS-funded services. The charts below show what we've found. Some of this analysis is found in a report published by the IBO last week. But with that agency's assistance, we chose a very different—and we think very useful—way to report and understand the numbers. And we've included some data here that are not in the IBO report.

Most importantly, in our charts and in the text below, all of the dollar figures are adjusted for the impact of inflation. In buying power, a dollar in 2010 had much less value than a dollar in 2000. Year after year, inflation wears away at the dollar's value. We believe inflation-adjusted dollars are a more logical way of comparing government spending over the years, rather than simply listing the actual (or "nominal") dollars spent each year in their value at the time. Why? Because the cup of coffee I bought at the deli for $1.45 this morning cost me just 65 cents in 2000. Much the same is true for the cost of salaries, benefits, office leases and all the other expenses that go into providing city-funded services.

When we adjust for inflation, for example, the $903.5 million that New York spent on foster care in 2000 has the buying power of $1.3 billion in 2010 dollars. (The IBO mostly uses nominal, unadjusted dollar figures in its reports).

These numbers tell a somewhat more sobering story than we heard from the IBO last week.

Chart 1. The Sharp Drop

Foster care spending in New York City fell 40 percent from 2000 to 2010. Over the same period, the number of children in foster care declined by more than half. Foster care dollars go mostly to foster parents and to the nonprofit agencies that work with them, the children and their parents. (In all of these charts, we use the city fiscal year, which begins on July 1 and ends on June 30.)

Chart 2. Hundreds of Millions of Dollars Saved

As the overall cost of foster care plummeted, total spending on preventive family support services increased—but the change was relatively modest.

Chart 3. Child Protective Services Grows

Spending on child protective services—that is, the ACS Division of Child Protection's investigation of abuse and neglect reports—increased in the years following the murder of Nixzmary Brown in January 2006.

Chart 4: The Loss of Federal Funds

Foster care is paid for with city, state and federal government dollars. The federal contribution collapsed in the middle part of the decade, when city officials acknowledged problems with the way they had been documenting claims for foster children's eligibility for funding under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act. So, despite the stunning decline in the number of foster children, the contribution to foster care from state coffers changed only modestly. And the contribution from city taxpayers was volatile across the decade, mostly plugging the huge hole opened up by the loss of federal funds.

Chart 5: Who Pays for Preventive Programs?

As with foster care, funding for ACS preventive family support services comes from the city, state and federal governments. The portion paid for by the city was lower in 2010 than in 2000. Since an agreement reached in 2006, an increase or decrease in city tax levy funds spent on preventive services is amplified by the state, because Albany matches local dollars spent on these services with a formula of its own.

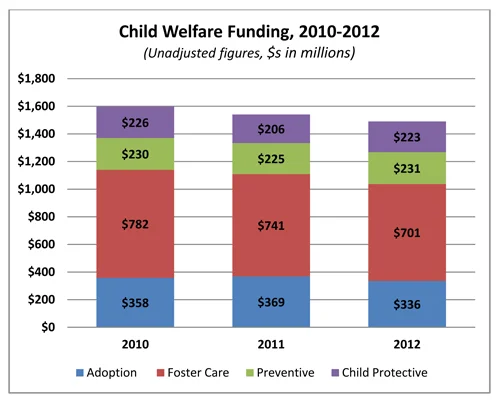

Chart 6: Preventive Services Funding Today

In June 2011, the Bloomberg administration agreed to "baseline"

ACS preventive family support services into the city budget at $230 million, almost exactly where it stood in 2010. This means that for the foreseeable future, the City Council may not have to fight to restore funding for preventive services every year. Dollars from the city still cover only a modest 20 percent of the preventive budget. (The figures in charts 6 and 7 are not adjusted for inflation, because they are so recent. The 2010 amount is actual expenditures. The 2011 and 2012 figures reflect what the city budgeted for these services.)

Chart 7: Foster Care and Adoption Almost Below $1 Billion

This final chart shows the four major areas of child welfare funding in New York City, excluding core administrative services. The "Adoption" category is mostly made up of subsidies provided to adoptive families. (Nearly 80 percent of the city"s adoption budget comes from the state and federal governments.) One interesting note: In Fiscal Year 2012, for the first time in decades, the combined budget of New York City foster care and adoption services is close to falling below $1 billion. If current trends continue, that may indeed happen in 2013.

An important acknowledgement: Thanks to the IBO and analyst Kate Maher for their help crunching these numbers.

News Brief: Are Foster Care Visiting Reforms Vulnerable?

BY ABIGAIL KRAMER

September 23 , 2011—In the wake of a mom’s abduction of her eight children from a foster care agency in Queens early this week, some child welfare practitioners and parent advocates are uneasy, worried that the city could roll back hard-won changes that have made foster care a little friendlier to kids and their parents.

The abduction took place Monday, when Shanel Nadal fled with her eight children during a supervised visit on the grounds of Forestdale, Inc., one of the city’s more highly rated foster care agencies. The Administration for Children’s Services announced it will launch an investigation.

Advocates fear the results—along with critical press and political reaction to the incident—could push foster care agencies to set more draconian standards for visits between parents and their kids. “Absolutely there will be blowback,” says Mike Arsham, executive director of the Child Welfare Organizing Project, a self-help and advocacy organization for parents involved in the system. Too often, he says, “this is how policy is formed in this city. We look at the worst possible cases and we generalize to all parents.”

When children go into foster care, ACS’s standard is to allow a visit with parents as soon as possible after being removed, and then twice per week thereafter. Regular visits are considered critical to maintaining bonds between parents and their kids, most of whom will reunite with their families eventually, and many of whom return home within a year.

Over the past decade, the city has substantially reformed visiting practices to make them more comfortable and productive for families. Ten years ago, parents were lucky if they spent two hours a month with their kids, says Tanya Krupat, a program director at the Osborne Association who headed an ACS commission to investigate and overhaul family visiting. In response to a 1999 legal settlement, the administration doubled the frequency with which families are entitled to visits and worked with foster care agencies to improve the spaces in which visits happen. More recently, ACS funded an effort to take some supervised visits out of foster care agency offices altogether, allowing community organizations to host them in neighborhood settings like parks and libraries.

Forestdale, where the abduction took place, was one of the agencies to embrace visiting reforms most wholeheartedly, working with a consultant to make visits less geared toward surveillance and more conducive to families spending happy, high-quality time together, says Krupat.

Visits give parents the chance to demonstrate they are capable of caring for their kids. “Workers need to know that visits are improving with each visit, that parents are engaging better, meeting the needs of their children, having happy visits,” said Paula Fendall, director of ACS’s Office of Family Visiting, in an interview conducted several weeks ago for a story on visiting that will appear in the upcoming issue of Child Welfare Watch. “That’s the only way they can move forward to reunification.”

But child welfare reforms are particularly vulnerable to a crisis, whether it comes in the form of budget cuts, a single incident like a child’s death or injury, or the exposure of poor practices. The fear, in this case, is that demands for higher security could force agencies to step back to a more institutionalized approach to visiting.

“I would hate to see the pendulum swing back,” says Bill Baccaglini, executive director of the New York Foundling, a foster care agency. “Was there a lapse in this case? Yes. But you can’t let these things get so darn mechanical that a mother never has 30 seconds alone with her kids.”

Arsham of CWOP worries that an increased focus on security could push foster care agencies to reduce the number of visits they offer, since they’ll have to provide more personnel to supervise them, and return the system to a model of visiting that’s damaging to parents and kids.

“You’re sitting in a cubicle with your child and a case worker who is writing notes on you, which often say that your interactions with your child seem strained,” says Arsham. “Well, you’re sitting in a freaking cubicle with somebody writing notes on you. If that’s not strained, you’re not human.”

News Brief: City Youth and the NYPD

BY ABIGAIL KRAMER

May 5, 2011—Amid the flood of analysis that followed the NYPD's release of data on its use of "stop, question and frisk" policing tactics, researchers recently released a survey showing widespread mistrust of police among 1,100 New Yorkers between the ages of 14 and 21.

The survey was conducted by the Polling for Justice project at the City University of New York, a collective of youth and adult researchers who developed the questions and distributed them through their own networks and those of community organizations. The participants were not as demographically representative of the city as a random sample would have been—nearly two-thirds of respondents were female and just 9 percent were white (whites accounted for 22 percent of the city's young people in the 2010 census).

Nevertheless, researchers set out to have a pool that reflected the racial, ethnic and socioeconomic differences among city public high school students and for the most part they did. Survey participants were geographically dispersed across all of the city's boroughs except for Staten Island.

Nearly half of the young people reported having negative interactions with police in the previous six months. Just 20 percent said they would feel comfortable going to the police if they needed help.

The survey data were collected in 2008 and 2009, when the NYPD used stop and frisk tactics on young people aged 14-21 more than 416,000 times, according to the CUNY researchers' analysis of NYPD data. This amounts to nearly 40 percent of all such stops.

The NYPD data show that young people were frisked in the majority (61 percent) of the stops and 1 percent of stops resulted in the discovery of a weapon. They also show that young people were stopped at an average of once every 90 minutes in high-poverty, majority black and Latino neighborhoods like East New York and Brownsville, Brooklyn, while whiter, wealthier areas averaged one stop every 18 hours.

By pairing the NYPD data with young people's accounts of their experiences, the researchers sought to document details and nuances that don't show up in the official numbers. "Young people are particularly vulnerable to the ebbs and flows of public institutions and local environments, yet they are seldom included in the discussion on what their experiences have been, what needs to change, and in what ways those changes should happen," says Brett Stoudt, a professor at CUNY's John Jay College of Criminal Justice and one of the lead researchers on the survey.

Young people who reported negative incidents with police were likely to have experienced them multiple times over the previous six months, with more than 40 percent reporting three or more stops. Twelve percent of the survey participants reported unwanted sexual attention from the police, or that they were touched inappropriately during a search.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and questioning youth were significantly more likely to have experienced negative interactions with police (61 percent) than young people who identified as straight (47 percent.)

Unsurprisingly, young people's perceptions of their own interactions with police corresponded with their general feelings about the NYPD. Among the survey participants who reported having only positive interactions with police, nearly 70 percent agreed with the statement that "in general, the police in NYC protect young people like me," though even that category of young people were unlikely (28 percent) to say they'd feel comfortable turning to police for help.

Among respondents who reported negative contacts with police, just 31 percent said they felt protected by police, and only 16 percent said they'd turn to police if they were in trouble.

That lack of trust may actually facilitate crime, says Stoudt, since it can limit police officers' ability to partner with community members. "We need to start considering what it means for the youth in NYC to grow up policed; to grow up as perpetual suspects because of how they look or where they live," he says.

The cycle of mistrust won't be broken until police are trained to look for individual behaviors that indicate possible criminal activities, rather than relying on contextual indicators like neighborhood or style of dress, says Delores Jones Brown, who directs the Center on Race, Crime and Justice at John Jay College. "A very small minority of young people, even in areas of high crime, are involved in serious criminal activities," she says. "Police need to learn to distinguish between those kids, in the same way as they do in white communities."

The NYPD press office did not respond to a request for comment. The Department of Probation's press office offered the following statement about the city's law enforcement strategies: "Since the early 1990s, there has been a 56 percent reduction in the number of New York City residents sent to state prison, thanks in large part to the NYPD's success in driving down murder and other serious crime. The city has also successfully reduced the number of youth who are detained in New York City or placed in upstate facilities. Both of these reductions speak to our ability to protect public safety while ensuring that all youth—including those who are most at-risk-have the opportunity to become successful members of their communities."

Photo: Stephane Bazart photography/flickrCC

News Brief: Brooklyn's Home for Juvenile Justice

BY KENDRA HURLEY

April 20, 2011—New York State is moving forward with plans to open its first psychiatric residence for kids with mental illness in the juvenile justice system. The planned facility, which will take over the site of a soon-to-close Brooklyn psychiatric hospital, is part of a large-scale reform effort to keep kids close to their homes and in community-like settings. But the state's first job, according to the director of the organization recently chosen to run the facility, is to overhaul the building so it doesn't feel like a prison.

The building sits on a campus filling several blocks of Bergen Street in Brownsville. It's a sprawling, two story, L-shaped structure enclosed by a high iron fence with a sliding electric gate overseen by a guard booth. "They're acting like this is either a medium security prison or a target of terrorism," says Michael Pawel, who runs the August Aichhorn Center for Adolescents. "It's the antithesis of a community facility."

The state's Office of Mental Health Services (OMH) expects the new residential treatment facility (RTF) to be up and running by the end of the year, housing city teens who would otherwise be sent upstate to juvenile lockups. Though the residence will house only 24 young people, its opening reflects a critical shift in how the state aims to treat and house children with mental illness who wind up in the juvenile justice system.

Some 50 percent of young people in juvenile correctional facilities have been diagnosed with a mental illness, according to the Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS), which runs the New York State juvenile justice system. Advocates place that percentage even higher. The state has a long history of providing inadequate psychiatric care to these young people. A 2009 Department of Federal Justice investigation of four state juvenile justice facilities found that cases of children with mental illness were mishandled; young people were given powerful psychotropic medications without proper monitoring; and staff at the facilities used excessive force and restraints. Shortly after the investigation, the Department of Justice threatened to take control of four state juvenile facilities unless, among other requirements, children needing more services than the facilities could provide were transferred to more appropriate settings.

But appropriate settings for court-involved youth with mental illness have been hard to find. While some adolescents are sent to residential treatment centers funded through the city's foster care system, they rarely have the level of clinical supervision required for court-involved young people with mental illness.

State-licensed residential treatment facilities, which are funded by OMH, typically have lower staff-to-child ratios and richer clinical services than the residential treatment centers.However, they are also infamously difficult to be admitted to. Only one in New York City accepts children who are violent: Michael Pawel's Aichhorn Center.

It's one of the reasons OMH and OCFS selected Aichhorn over much larger social service agencies to run the new RTF. "This new program will really be able to manage some of the behavioral disruptions that the other RTFs aren't equipped to do," says Susan Thaler, director of children's services at OMH's New York City field office. "There is some expectation that these kids have histories of violence and running away and haven't been able to manage or receive treatment in other kinds of settings."

Thaler says the new program's Brooklyn location will make it easy for teens to visit with their families and will allow for a more natural transition when it's time to return home.

Pawel's plans for the residence, which he presented to OMH this month, are modeled after Aichhorn's adolescent psychiatric facility in Harlem, which currently houses some juvenile offenders. He proposed to break down the tall fence surrounding the building and add an entrance to the street to connect it to the neighborhood. On the inside, he wants to add carpeting and comfortable living room spaces and ditch the locks on the outside of bedrooms as well as the building's electronic "panic system," which staff at the psychiatric hospital now use to alert help with the touch of a button.

The building's living space will be divided into apartment-like units each housing a co-ed group of 8 young people."Having units co-ed is very unique and normalizing and helpful," says Pawel. "People tend to be calmer in co-ed groups."

Each unit will share meals in their own kitchenettes, family-style. And just like at the Harlem residence, mental health services will be folded into most every aspect of the young residents' lives—both while they're living in their units and in school. The site will have the equivalent of one full-time psychiatrist, three unit leaders, and two other therapists.

Pawel believes the program's most important challenge will be getting away from the idea that "might makes right."

"My understanding is that particularly mentally ill youngsters in OCFS facilities are being managed primarily by a lot of physical force," he says. "If you can get a group like this which is a very unhappy, very angry, very violent group and more or less eliminate the incidence of violence while they're being supervised, that's very good and I think that's going to be clear very quickly. And I think we can pull it off."

One internal Aichhorn study compared the outcomes of young people admitted to the organization's Harlem program with other teens who met the same admission criteria but were rejected because beds were not available. Using state court data, the study found that 39 percent of Aichhorn's alumni were subsequently arrested, compared to 60 percent of the group that was not admitted to the program.

Pawel hopes he can produce similar or better results at the new residence. Advocates are optimistic too, but say the new program should be only the beginning. "For far too long, the juvenile justice system has been used to warehouse children with mental illness; an approach that fails both children and the public," Gabrielle Prisco, director of the juvenile justice project at the Correctional Association of New York, said in a written statement. "We hope that this is only one part of a larger transformation from a punitive juvenile justice system to one that meaningfully serves the needs of children, builds upon their strengths, and maintains their connections to their families and communities."

Photo: Sandeep Prasada

News Brief: State Budget Roundup

BY ABIGAIL KRAMER

April 7, 2011—Youth programs will shrink, families will lose childcare subsidies, and housing programs for runaway and homeless teenagers will disappear.

Governor Andrew Cuomo and members of the New York State legislature have given themselves plenty of credit for passing an on-time budget that closes a $10 billion deficit without raising taxes. The biggest spending cuts are in education and health care, but there are substantial changes in funding for other programs that serve the state's low-income children, youth and families. Read on to see how key services will fare in Fiscal Year 2011-12.

JUVENILE JUSTICE

Shrinking the system:

The legislature approved Governor Cuomo's plan to downsize the juvenile justice system by nearly 400 beds. They balked at his proposal to permanently repeal the requirement that state officials give the legislature 12-months notice before closing underused juvenile jails.

The notification requirement has traditionally been defended by guards' unions and upstate legislators whose constituencies depend on jails and prisons for jobs. This go-round, they reached a temporary compromise that shortens the waiting period to 60 days. As of April 2012, the one-year rule will be back in effect.

The same deal applies to adult prisons, as well as mental health facilities operated by the state.

Detention dollars:

Historically, the state has reimbursed cities and counties for half the cost of running juvenile detention centers, where young people are held while they wait for a court hearing or transfer to longer-term, state-run correctional facilities.

In his February Executive Budget proposal, Governor Cuomo anticipated capping detention funding at $30 million, saying he wanted to save money while also giving localities the incentive to send young people to community-based programs instead of holding them in detention centers. The Bloomberg administration and legislators pushed back, arguing that local governments need both time and money to ramp up their alternative programs.

Instead, the enacted budget raises the cap to $76 million. The state will allow local governments to choose whether they'll spend this money on detention—which the state will continue to reimburse at 49 percent (up to the cap)—or divert some of it to alternative-to-detention programs, for which the state will pay a 62 percent share. Another $8.2 million will be disbursed to cities and counties exclusively for community alternatives.

While the state plan aligns, in many ways, with New York City's five-year-and-running effort to divert kids out of detention centers and into community programs, Mayor Bloomberg's preliminary budget projects no decrease in spending for city detention centers next year, according to an analysis by the Independent Budget Office. Nor does the city expect to see a new benefit from the state's alternative-to-detention funding, since its programs are already reimbursed by the state at a 62 percent rate.

Improving state lockups:

Despite the plan to cut beds and close facilities, the state budget designates $38 million over the next two fiscal years to increase staffing and improve mental health, education and other services in state-run juvenile jails. These improvements come as a response toserious criticisms and a federal lawsuit over poor conditions and brutal treatment in the state's juvenile lockups, but they mean that the city—which has drastically cut the number of kids it sends to the state over the past five years—will likely see another increase in the amount of city tax levy funds it must contribute to the maintenance of the state correctional system.

CHILD WELFARE

Kinship Guardianship:

Most state money for foster care is lumped into the Foster Care Block Grant, which is to be maintained in the new budget at $436 million. This year, some money from the block grant will pay for Kinship Guardian Assistance, a new program that allows foster kids to leave the formal child welfare system and live with a guardian, who will receive a stipend. In most cases, this guardian will be a relative with whom the child has already lived in foster care. One advantage: the child retains his or her legal relationship with parents, which is not the case in an adoption.

The program helps children avoid the trauma of being permanently cut off from a parent. But there's a debate over whether it should be paid for out of the Foster Care Block Grant. "That money is supposed to be for kids in foster care," says Stephanie Gendell, a policy analyst at the Citizens' Committee for Children of New York, which advocated for the state to find separate funding for the program. "Taking that money sets a bad precedent."

"The Foster Care Block Grant is a limited resource and not intended for long term supports like guardianship, which is why the City advocated for the State to share the financial responsibility for this program in the same way that we do for adoptions," says John B. Mattingly, Commissioner of the City's Administration for Children's Services. The City wouldn't bear a significant financial impact in the current year, since families receiving the subsidy would be leaving the foster care rolls, but Commissioner Mattingly argues that the funding system ultimately places the full cost on local governments. "The concern is that there are no new dedicated resources and we know from past experience that block grant funding is unlikely to grow."

Adoption subsidies:

When kids are adopted out of foster care, their adoptive families usually receive financial support from local governments. The state has traditionally reimbursed cities at a significantly higher rate for adoption subsidies than for other foster care expenses. That way, localities had an incentive to get young people out of foster care and into permanent families.

Under the new budget, the state's share of adoption subsidies will drop from 74 percent to 62 percent—the same as for preventive services, child protection and other child welfare expenses. There are currently more than 27,000 children receiving adoption subsidies in New York City, at an average of $980 per month. The city plans to make up for state reductions with about $3 million in city tax revenue.

Sexually exploited youth:

The new budget eliminated a plan to build a $3 million safe house for sexually exploited youth—usually kids who've worked as prostitutes under the control of a pimp.

PREVENTION PROGRAMS

The state will continue to fund traditionally defined preventive services, which aim to stabilize struggling families and prevent their kids from ending up in foster care, at last year's reimbursement rate of 62 percent.

However, in his budget proposal, Governor Cuomo conceived of a new funding stream that would have lumped together a wide array of other programs that strive to keep kids out of the child welfare and juvenile justice systems.

The plan would have cut funding for home visiting programs for new mothers and babies, and as a result it would have made the state ineligible for millions of dollars from the federal healthcare reform act, according to budget analysts.

That proposal was ditched. In the enacted budget, the legislature restored last year's $23 million in funding for the state's largest home visiting program, Healthy Families New York. The state's other major home visiting program, the Nurse-Family Partnership, will lose $2 million in designated money but remain eligible for a competitive funding stream known as Community Optional Preventive Services, which will receive a total of just over $12 million, down from $24 million last year..

Other preventive programs will receive a total of about $21 million, or half the funding they received last fiscal year. These programs range from after-school services that keep kids off the street to temporary housing for runaway and homeless youth. (For a full list of the prevention programs and their allocated funding, see the Citizens' Committee for Children budget analysis here.)

CHILDCARE

The state's $393 million Child Care Block Grant, which helps cities and counties subsidize childcare for low-income families, will stay at the same level as last year. However, the state will lose nearly $50 million in federal childcare money that it received in the 2009 stimulus act.

The loss will be a hard hit for New York City, which has seen its own childcare costs rise by more than 60 percent since 2004, according to the IBO. In 2010, the city provided childcare subsidy vouchers to about 102,000 kids. This year, it plans to cut more than 16,000 of those vouchers, or about one third of the subsidies that currently go to families that aren't on public assistance. Many advocates have raised the concern that cutting childcare for working-poor families will push more New Yorkers into unemployment.

The budget provides $4.9 million to subsidize childcare for students at SUNY and CUNY colleges, and for childcare demonstration projects that provide care to working families whose incomes make them ineligible for city vouchers. Those programs received $7 million from the state last year.

YOUTH PROGRAMS

The Summer Youth Employment Program, which provides work experience to young people around the state, has been a New York City budget football for years. First the funding gets cut, then advocates scramble to get it restored, usually by the City Council.

This year, the governor proposed to kill state funding for the program altogether. The legislature reversed that move, restoring the full $15.5 million that the program received last year. However, New York City still faces a loss of 12,000 summer youth jobs due to a loss in federal stimulus funding, according to Anthony Ng, Director of Policy and Advocacy at United Neighborhood Houses.

The state will also lose $4.5 million for Advantage Afterschool programs, which provide activities for kids in the afternoon. Total state funding for the programs will be $17.7 million.

PUBLIC ASSISTANCE

In 2010, the state decided to implement a three-phase, 33 percent increase in public assistance grants, which hadn't been raised in the previous 20 years. This year's budget delays the third and final increase by a year, putting it off until July 2012.

The legislature rejected a proposal by the governor to apply harsher sanctions to families where a parent fails to comply with work requirements. As in the past, sanctions will apply to the portion of benefits that go to support the parent, rather than benefits allocated to the entire family.

Child Protection: An Insider's View

March 25, 2011—Not long ago, Child Welfare Watch interviewed frontline child protection workers about their job. We were considering writing an article about the stress they experienced, and what might be done to reduce it. One major source of stress for many, though, has no easy solution: the constant worry that they might miss something that will haunt them.

Below are excerpts from one of those interviews as told to reporter Kendra Hurley. We've granted this investigator anonymity, although she didn't ask for it at the time. That was before two former ACS frontline workers were charged this week by the Brooklyn District Attorney with criminally negligent homicide for mishandling the case of 4-year-old Marchella Pierce, who died last fall.

The comments below are just one person's view, but some of her experiences are widely shared. She intended none of this to be interpreted as excusing any investigator's failure to do their job. Far from it. In her words:

I always wanted to work here and now that I'm here I'm like, "You've gotta be kidding." When the school year picks up, we just get case after case, and once a case is generated the clock is ticking. It's like a ticking time bomb. It's a juggling act. It's like that guy in the circus spinning those plates, and that's how I feel, I'm spinning those plates, and I can't drop one because that means a kid could be dead or a kid could be hurt.

So many responsibilities fall on my shoulder that I'm not really sure I can do this. I'm responsible not only for assessing the child's safety at that moment, I'm responsible for risk, which is the future. I'm responsible for looking into the future.

You could leave a house where you have a case and something bad happens there the next day and they could say, "Miss P, you needed to be able to see into the future." These are people's lives and it scares me every day I turn on my TV and see the news. I see a story where something went wrong with a child known to ACS and I'm thinking, "Is it my house? Is that my kid?"

I've been here almost a year now. I still get a rush when I get a case. I get excited. I want to go see what's going on. If I can't get in a home, I want to find a way. I'm one of those workers who's not afraid. I walk into any housing development where it's obvious there's drug trafficking, people hanging out, you know, and when I'm knocking at the door there's nothing in me that's saying, "Are you sure?"

It makes me feel good to know that I am trying to save a kid's life. I love the fact that my families look at me and say, "I need your help." They depend on me and I follow through. I get a sense of fulfillment. Sometimes you are a wakeup call for families. I've had my clients say "thank you."

I learned a lot from the academy where caseworkers get trained, but it's not the same as when you're in the field. I'm not used to getting these cases this fast and these cases just keep coming in. Even if it's a bogus case, even if it's a girlfriend calling a case on her ex-boyfriend who she's mad at, I still have to treat that case as if it's real. I still have to follow through with the investigation.

In the training unit, you get a page-long of directives on how to ascertain the relationship of a great great grandma who lives in Georgia, who has nothing to do with the case. But in the field I don't have enough time to dig into great granny's life. I don't have enough time to sit and figure out if there is domestic violence and dissect that.

In past jobs I've worked with different populations from youth to residential treatment facilities. I have a strong skill set. I have qualities I know I'm good at. But it's not helping me here. Here, I'm up against the clock. I'm not sitting down and servicing families the way I think they should be serviced.