April 17, 2019

Creating Environmental Justice at the Local Level

A Q&A with environmental policy expert Dr. Ana I. Baptista.

With Earth Day approaching, Urban Matters spotlights a new report, “Local Policies for Environmental Justice,” from the Tishman Environment and Design Center (TEDC) at The New School. It reviews a growing movement to enlist local governments in stopping and reversing environmental health and safety hazards in low-income areas and communities of color that the report also calls "environmental justice communities." We asked Dr. Ana Baptista, TEDC’s associate director and the report’s principal author, about it.

Urban Matters: The report starts with a damning review of how local governments have historically saddled low-income areas and communities of color with environmentally hazardous industries and public facilities. But then you and your colleagues write: “If zoning and land use policies got us into this mess, they have the potential to get us out it.”

Briefly unpack that argument. How responsible have local governments been in jeopardizing health and safety in these communities? And why should those communities now rely on those same governmental bodies to turn things around?

Ana Baptista: Local governments have been and continue to be inextricably linked to development of segregated and polluted landscapes. Cities and towns have historically used zoning and land use planning to set the terms of development. This power has been used to separate unwanted land uses as well as people of color from wealthier, whiter areas. This was essentially the purpose of early land use laws, to protect property values via exclusion and segregation. This process, along with racially motivated real estate, banking, and economic policies, led to co-location and concentration of industrial, noxious land uses and de-valued residential communities of color and low-income communities.

The idea of reforming land use and other local policies in favor of environmental justice does not so much rely on government bodies to do the right thing. Rather, it demands that they be more accountable to impacted communities. The policies reflected in this report are largely products of community-based advocacy and many years of local organizing to force municipalities to codify and institutionalize reforms.

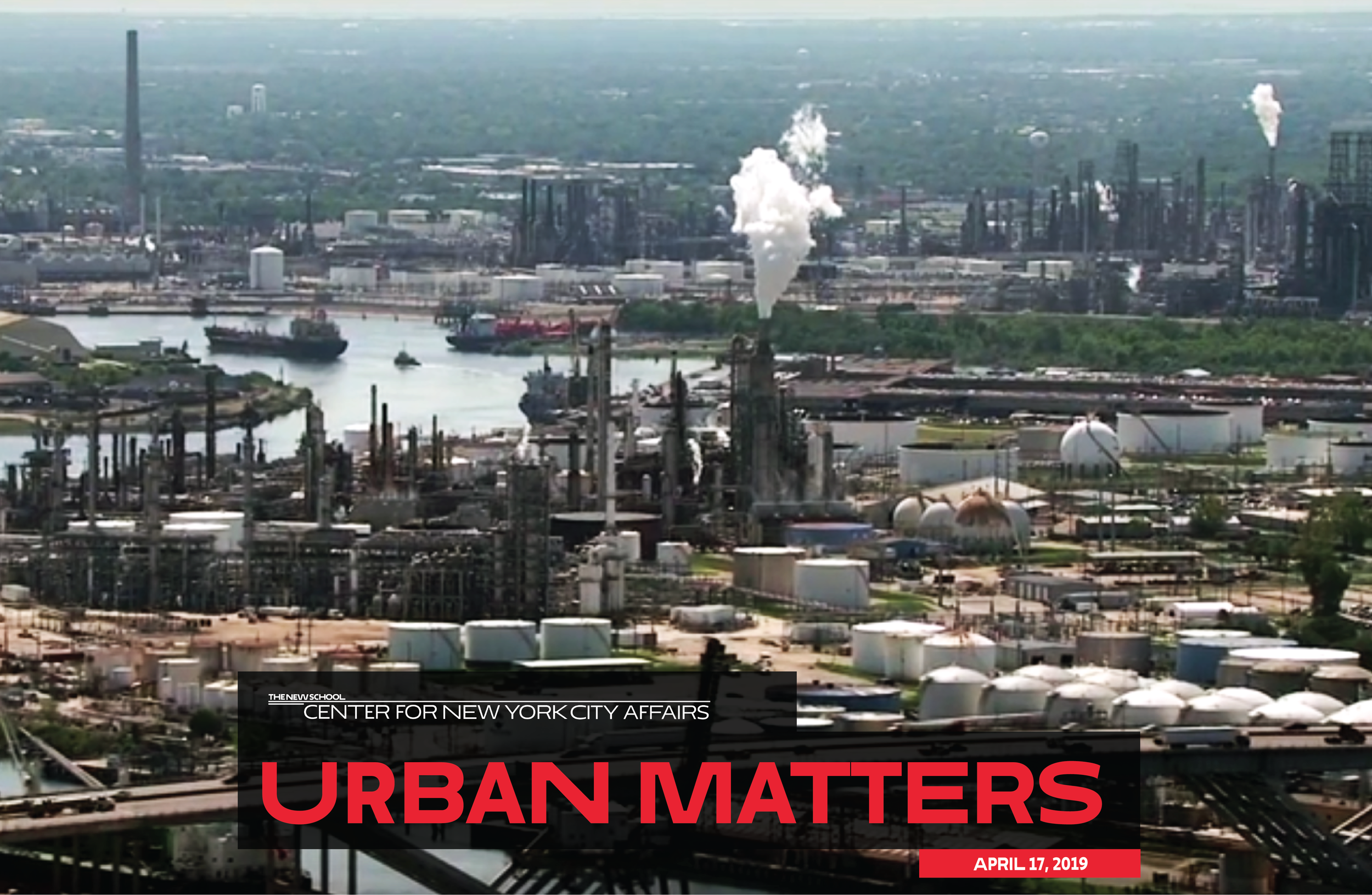

UM: You analyze some 40 such reforms, including new ordinances in Baltimore, Oakland, and other cities that ban opening or expanding facilities that process, store, or transport petroleum products. What’s the relationship between those measures and the huge growth in fossil fuel fracking?

Baptista: That growth has added pressures to the fossil fuel infrastructure, much of it located in environmental justice communities. Fracking’s growth has also meant that many suburban and rural communities are beginning to see this infrastructure for the first time in their backyards in the form of pipelines and frack fields. The ordinances reflect ongoing struggles over exacerbation of existing injustices in the form of expanded or intensified fossil fuel facilities.

UM: Under the Trump Administration there has been a well-documented drop in enforcement actions against alleged polluters by the federal Environmental Protection Agency. EPA staffing and funding have shrunk. Given that, how important, and how effective, are local measures in offsetting an environmental policy vacuum at the national level?

Baptista: Local measures are critical at a time when the federal government is seeking to undermine and retract its enforcement and regulatory role. They allow a measure of oversight and accountability that is more accessible to local residents. It’s also a more direct tool to intervene early in the development process, before the regulatory process is triggered. It allows flexibility to consider more wholistic planning, visioning, and community engagement. But local measures alone are not enough. Environmental justice also requires state and federal interventions because most environmental regulatory decisions are carried out by state and federal entities. We need affirmative policies at every level of government.

UM: Your study describes California’s recently passed “Planning for Healthy Communities Act.” It sets out what local governments must do to identify low-income communities disproportionately affected by pollution, and then help them overcome the effects. You call it “by the far the most wide-reaching state-level effort to embed environmental justice considerations” into local land use decisions. Is this the shape of things to come?

Baptista: California SB100 is an innovative and comprehensive approach to institutionalizing environmental justice into local planning efforts. I believe it will increasingly be the norm among local planning agencies, as communities across the country seek action and recognition of environmental justice issues. Many planning schools and departments are already embedding environmental justice into their work, pushed by the environmental justice movement to respond to local demands.

UM: This report was done in collaboration with environmental justice groups in an aging industrial corridor in southeast Chicago. That’s a pretty long way from The New School. How did that come about, and what was it like?

Baptista: This partnership came about through the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Chicago office, which was already providing technical and legal support to “EJ” organizations on local struggles over polluting developments. NRDC knew about my involvement in developing Newark’s Environmental Justice and Cumulative Impacts Ordinance and my knowledge of land use and planning issues. Also, some of the EJ organizations, like the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, were familiar with me through our shared involvement in a national coalition called the Moving Forward Network. This was a great partnership. I really identified with the struggles the groups in Chicago were facing in trying to wrestle control of local land use from powerful developers and politicians. I felt privileged to partner with them and produce a resource I wish I had had when we worked on Newark’s ordinance.

UM: Last question: How has your report been received, and what impact do you hope it will have? What are the next steps?

Baptista: The report has been very well received. I believe it’s been useful to environmental justice groups in Chicago as they push City agencies to implement forceful environmental justice policies. Local politicians and agencies can no longer throw their up hands and say they can’t or don’t know how to do it – because the report illustrates that it can and has been done by many others.

We are continuing to share findings of the report in a variety of venues. The next steps are publishing results of in-depth case studies on implementing California’s Green Zones and Newark’s Environmental Justice and Cumulative Impacts Ordinance. We want to better understand the challenges and opportunities that arise once policies are passed and communities seek full implementation.