November 1, 2017

Congestion Pricing and the Working Poor: Few Would Pay, Many Could Benefit

By Nancy Rankin and Irene Lew

Next month, an advisory panel appointed by Governor Andrew Cuomo is expected to deliver its recommendations for coming up with the hundreds of millions of dollars that experts agree is needed to make badly needed fixes to New York City’s ailing, 113-year old subway system. That will set the stage for what’s likely to be a major element in the budget the Governor sends to the State Legislature in January. (Because State government tightly controls the power to impose most taxes and many fees in the city, and because Cuomo appoints a majority of the board of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority that runs the subways, the key decisions about funding subway upgrades will be made in Albany.)

Cuomo has already signaled that his administration may revisit the idea of congestion pricing–a concept that was championed by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2008, but that failed to gain the necessary traction in Albany despite garnering the support of business, labor, and environmental groups. While there are no details on what the governor’s plan might entail, previous congestion pricing proposals have called for a combination of charging fees to vehicles traveling below 60th Street in Manhattan, placing tolls on four currently un-tolled East River crossings to Manhattan, and other transportation-related fees or taxes to fund transit and infrastructure improvements.

For his part, Mayor Bill de Blasio has proposed creating an alternative recurring revenue stream to pay for transit improvements by imposing a modest increase in the state’s “millionaire’s tax” on the city’s wealthiest residents. The mayor has also called for using a portion of the proceeds from an expanded millionaire’s tax to fund “Fair Fares.” That’s an initiative advanced by the Community Service Society (CSS) and the Riders Alliance and supported by a broad coalition of anti-poverty groups, unions, advocates, faith-based leaders, and elected officials to provide half-priced bus and subway fares to working-age city residents with incomes at or below the poverty level.

With action on these issues likely to come early in the new year, CSS decided to examine the potential impacts of both congestion pricing and Fair Fares on New York’s working poor. Our conclusion: Congestion pricing fees would fall on relatively few such outer borough residents, while dramatically more would benefit from Fair Fares funded from either congestion pricing revenues or an enhanced millionaire’s tax.

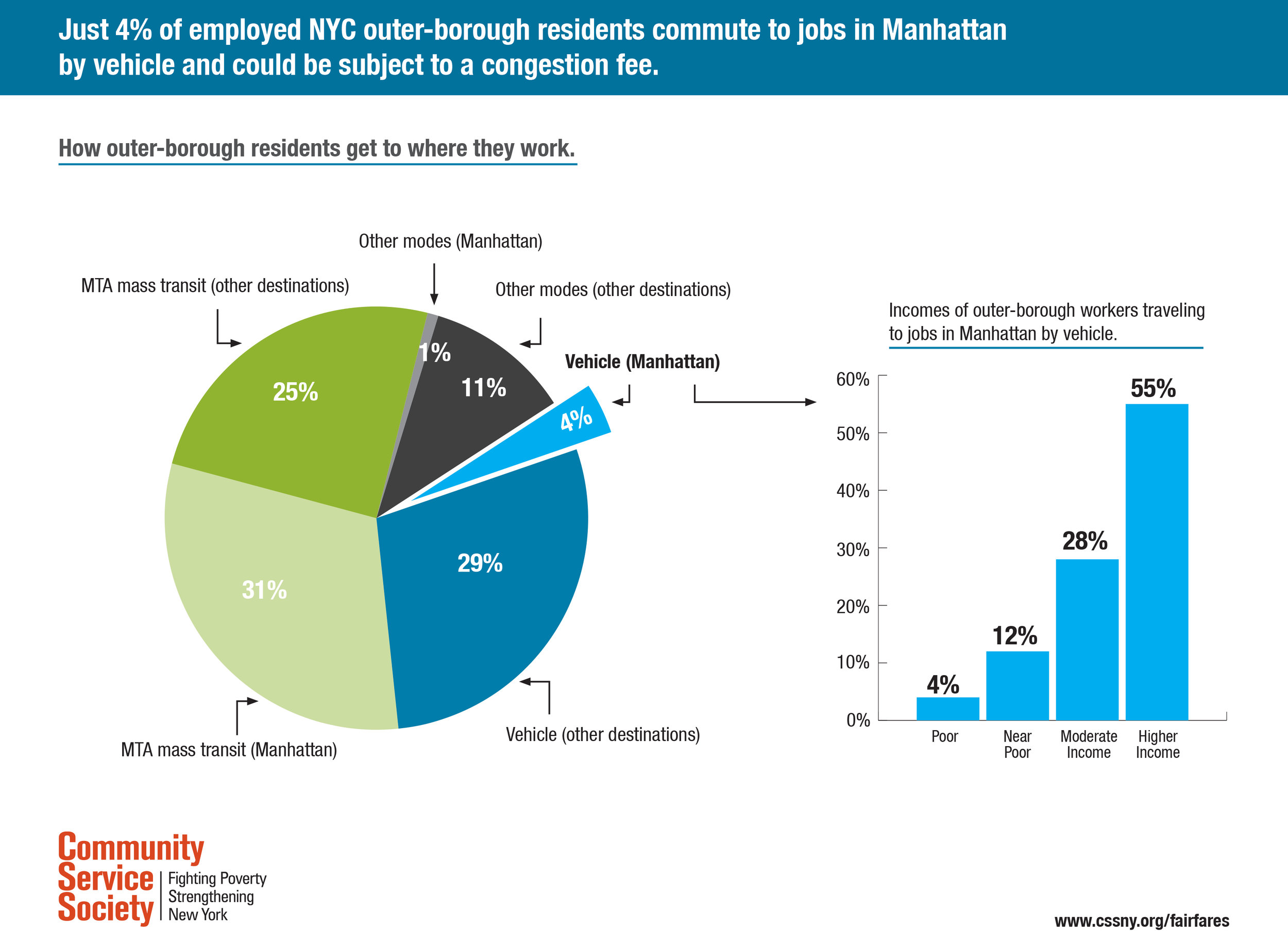

Specifically, our analysis found that just four percent of the city’s outer borough working residents commute to jobs in Manhattan by vehicle and could be subject to a congestion fee. This compares with 56 percent of outer borough residents who use mass transit to commute to work in Manhattan, the other boroughs, or outside the city. Another 29 percent drive to other destinations besides Manhattan for work. And 11 percent either work from home or use other modes of travel to work outside Manhattan, including biking, walking, or taking a ferry. Just one percent walk, bike, or take the ferry into Manhattan for work. Of the four percent who drive to jobs in Manhattan, the overwhelming majority have moderate and higher incomes.

CSS also found that only two percent of the city’s outer borough working poor could potentially pay a congestion fee as part of their daily commutes. This compares with 58 percent who rely on public transit and who would theoretically benefit from a congestion pricing plan that raises money for both improved transit services and fare discounts.

To the question of who actually gains from improved public transit and half-priced fares for the working poor, CSS found that approximately 2.2 million city residents rely on public transit to get to work, including 190,000 working poor who would also be eligible for half-priced “Fair Fare” MetroCards. Conversely, CSS found that 118,000 outer borough residents who get to work by driving or as passengers would potentially pay a fee – but that would include only about 5,000 who are among the working poor.

In short, for every New York City outer borough commuter who would pay the new tolls, 18 would gain from transit upgrades. And the city’s working poor would benefit by a dramatically higher margin of 38 to one from a congestion pricing revenue stream used to fund both transit upgrades and the Fair Fares discounts for the lowest-income riders. Or as CSS President and CEO David R. Jones, sums it up, “The high cost of riding the city’s buses and subways is pushing people into poverty. Whether New York adopts a congestion pricing model to fund subway system upgrades or gets behind the mayor’s millionaire’s tax proposal, we need to think progressively about leveraging resources to make our mass transit system accessible to all New Yorkers.” CSS is not the only organization with this viewpoint –already groups who are unquestionably dedicated to the interests of low-income New Yorkers are coming to the same conclusion.