More than a year and a half after a pair of widely publicized child deaths, New York City's child welfare agency continues to investigate a dramatically higher number of families than in recent years, according to data published by the Administration for Children's Services (ACS).

Once families are under investigation, ACS has become far more likely to bring them to court, rather than allowing them to resolve their cases voluntarily. Between October 2016 and May 2018, ACS filed Family Court petitions involving close to 26,000 children—a 54 percent jump over a corresponding timespan beginning in 2014.* Over the same period, ACS reported close to 30 percent more so-called "emergency removals" than in previous years, taking a child out of a home even before the case appeared before a Family Court judge.

Observers inside and outside ACS say the surge of cases is driven by heightened anxiety and caution—both among members of the public, who are calling in more reports of possible child abuse and neglect, and among child welfare staff, who are responding to those reports more aggressively.

But the resulting system overload may have negative consequences for kids, observers say, subjecting vulnerable families to unnecessary surveillance while reducing attention on children who might be in real danger.

The increased burden is apparent across the City's child welfare system: In the past 20 months, caseloads have gone up dramatically among frontline workers responsible for investigating reports of neglect and abuse. Families sit on waitlists—sometimes for months—for services intended to make sure children are safe and healthy at home. And attorneys say the influx of cases has overwhelmed Family Courts throughout New York City, exacerbating chronic delays and deferrals that impact every family in the system.

"Hearings are not happening quickly. Judges are struggling with several emergency hearings at a time, half an hour one day, half an hour the next," says Lauren Shapiro, the director of the Family Defense Project at Brooklyn Defender Services.

The result, attorneys say, is a new level of dysfunction across Family Court—a place where it was already common for a single judge to schedule two or three hearings for the same half-hour timeslot. "We're seeing so many cases where there's no court report available, or the ACS case worker isn't there," Shapiro says. "The family comes back to court over and over where nothing gets done."

The surge of activity began in October 2016, after the widely publicized killing of a 6-year-old named Zymere Perkins, who was beaten to death in his home less than two months after his child welfare case was closed. Three-year-old Jaden Jordan was killed in November of the same year, after an ACS investigator, responding to a report of abuse, failed to find his address.

ACS faced scathing criticism in the news media; then-Commissioner Gladys Carrión resigned from the agency. Under new leadership, ACS instituted reforms to its workforce training program, significantly increased funding for preventive services, and established new oversight systems for the most critical cases.

“Commissioner [David] Hansell has made top-to-bottom improvements at ACS, strengthening our child-protective work and expanding the services we provide to support families," said ACS spokesperson Chanel Caraway in an emailed statement. "Our top priority is protecting the safety and wellbeing of New York City’s children.”

Historically, however, tragic and high-profile child deaths have always led to increased pressure on the child welfare system. In the 20 months after Perkins's death, the State received more than 118,000 reports of possible neglect and abuse—a nearly 11 percent increase over a corresponding 20-month period before the crisis. (See below for a detailed data analysis of ACS activity.)

Once ACS is investigating a family and finds credible evidence of abuse or neglect, it has a considerable array of options, including offering voluntary services such as family therapy or drug treatment, and then closing the case. Since October 2016, however, the agency has taken a much higher percentage of cases to Family Court, petitioning a judge to order the family to engage in services while ACS monitors children’s safety.

Much of the increase in court petitions has been driven by an evolving approach to families dealing with domestic violence, said Andrew White, a deputy commissioner at ACS, speaking at a public forum. Both Zymere Perkins and Jaden Jordan were allegedly killed by their mothers’ partners, and relationship violence was reported to be a problem in both homes.

Notably, the increase in investigations and court filings has not led to an equally drastic growth in the number of children removed from their homes. In the 19 months after Perkins's death, the City placed approximately 6,250 children in foster care—a rise of about four percent over the previous, corresponding time span. This increase is much smaller than those that have taken place after other, widely publicized child deaths in the past decade.

Even a moderate increase in foster care placements, however, represents the reversal of a longstanding trend. Over the past several decades, the City has drastically shrunk the number of children in foster care—down from more than 45,000 in the mid-1990s (when the union representing caseworkers promoted slogans like, "When in doubt, pull 'em out,") to the current, near-record-low of approximately 8,600.

That reduction was made, in large part, due to growing recognition that, for most children, being separated from a parent is a terrifying and deeply traumatic event.

"It's clear that ACS is trying to ensure that children can stay home safely as much as possible," says Ronald Richter, who served as the commissioner of ACS from 2011 to 2013, and subsequently as a Family Court judge. "It's admirable that they're really trying not to just bring kids into care."

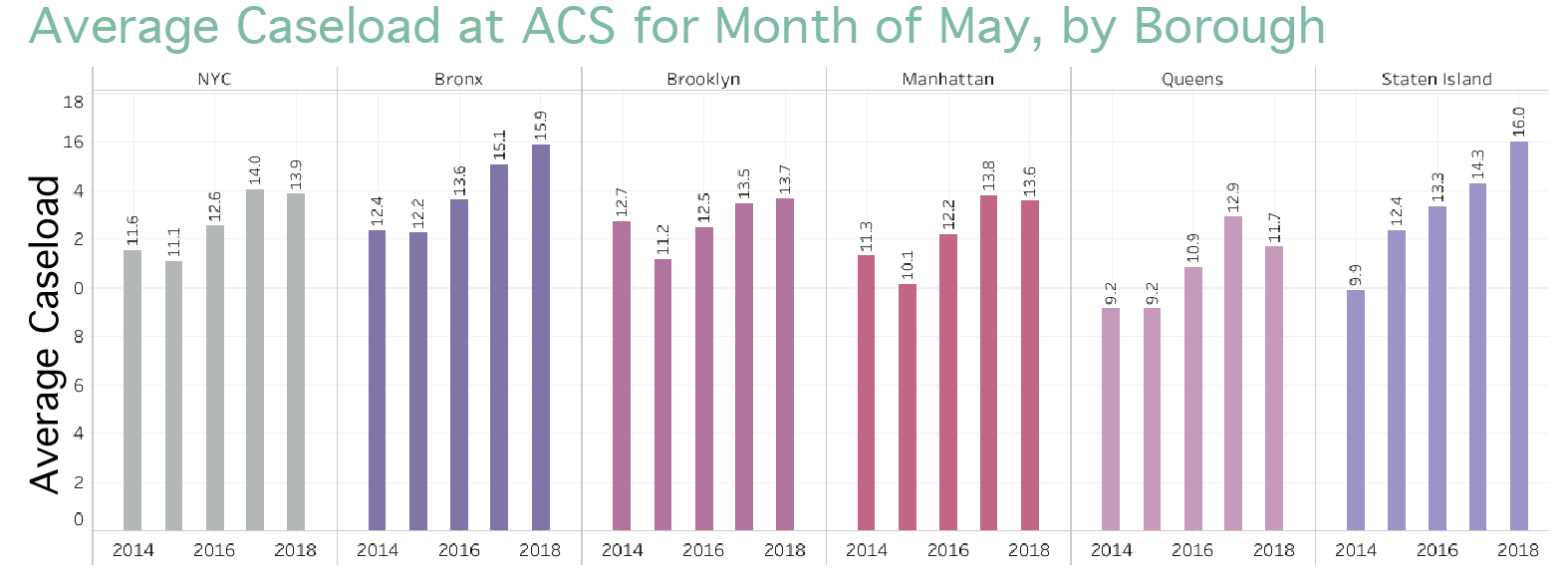

But the escalation in neglect and abuse investigations has other consequences—starting with the caseworkers who conduct the investigating. According to ACS data, average caseloads among child protective workers have gone up, citywide, from 11.6 in May 2015 to 13.9 in May 2018. The increase is much starker in the Bronx and Staten Island, where caseworkers carry average reported caseloads of approximately 16.

Those numbers are worrying, Richter says. "A sustainable caseload in New York City is eight. If caseloads are at 14, your caseworkers are just not able to do what they need to do."

ACS has hired several hundred frontline staff in the past year, but child protective caseworkers are notoriously difficult to retain. "ACS may hire 300 people, but 40 percent are going to be gone," Richter says. "This is the hardest job there is."

Caseworkers who stay work long hours, making high-stakes decisions under intense pressure—often based on interactions with people who want nothing to do with them. Higher caseloads mean there’s a greater chance of missing something important or making a wrong call, said one longtime child protective caseworker, who requested anonymity because she's not authorized by ACS to speak publicly.

A lasting consequence of the crisis surrounding Zymere Perkins's death, the caseworker said, is that frontline ACS staff are more inclined to recommend that cases be taken to court, rather than allowing families to do voluntary services.

"At this point everybody's so afraid, they'd rather cover their ass,” the caseworker said. “Take the case to court and let the judge say no. Then we can document we tried. Nobody wants to end up with their face in the Daily News. They don't want to face criminal charges."

Once ACS decides to file a case, however, it's unlikely that a judge will dismiss it outright, says Richter, the former ACS commissioner and Family Court judge. "Judges may yell and get frustrated with ACS" for filing a petition without a strong enough cause of action, Richter says. "But they’re anxious: Maybe there's something here."

The most extreme choice child protective staff can make is what's called an "emergency removal"—in other words, taking a child out of a home before the case even appears before a Family Court judge. ACS data show a sharp increase in such removals: Between October 2016 and May 2018, ACS reported approximately 2,300 emergency removals—a 28 percent jump from a corresponding 20-month span before the crisis.

These numbers are partial, however, since they include only emergency removals that were approved by a judge on the first day that a case appeared in court. ACS does not publicly report emergency removal cases in which a child is reunited with his or her family at the initial court hearing, or in which the judge makes a decision after the first day. (Upon request, ACS did not disclose the total number of emergency removals.)

Anecdotally, lawyers who represent parents in Family Court say that ACS seems, more frequently, to be making emergency removals that aren't justified by a child's circumstances. "Those are the removals that are the most traumatic for children," says Emma Ketteringham, the managing director of the Family Defense Project at The Bronx Defenders. "They're often done in the middle of the night, without preparation. You find out five minutes before that your child is going to be removed."

The rise in emergency removals, Ketteringham argues, is the clearest indication that an over-reactive child welfare system can hurt children—especially in the context of the current conversation about children separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border. "With all of this attention being paid, nationally, to what removing a child from a parent actually looks and sounds like, it's no different when a child is removed from a parent here in the Bronx," she says.

For a fuller data analysis of ACS activity download the brief.

Endnote

1. Child welfare activity fluctuates according to annual patterns. For this reason, we select corresponding months when making comparisons between different years. (For example, most of our bar charts compare October 2016-May 2018 to October 2014-May 2016, rather than simply 20 months before and after October 2016). In all cases, we include data through the most recent month for which they are available.

All data come from ACS monthly Flash reports.