Living Apart: Homelessness and the Loosening of Family Ties

By Kendra Hurley

Today in some New York city neighborhoods, eviction has become as common as rats in the subway; bouncing from one temporary home to another has become a way of life. When the goodwill in those temporary homes runs dry, parents begin to bargain. Sometimes a child ends up staying on with a grandma or another relative while her mother lives elsewhere and tries to get back on her feet. Other times, an entire family will turn to New York City homeless shelters.

A record number of around 23,000 children are living in City shelters, with families spending an average of over 400 days in those shelters. Nearly half of these kids are under 6 years old. Most of the rest are of school age. The Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness estimates that about one out of eight New York City public school students have been doubled up, in shelter, or without shelter sometime during the past five years, adding up to over 127,000 students. Together these children represent a large swath of an entire generation of New York City children who are growing up homeless.

The policy conversation about how to help these kids typically focuses on education, on how to enroll the youngest kids in preschools and help the school-aged ones stay connected to familiar schools and miss fewer classes. But there’s something that impacts kids in an even more urgent, visceral way: the strong connection between homelessness and family breakup.

Missing from the dialogue around homelessness has been a frank discussion of the complicated, myriad ways in which the experience of losing one’s home threatens to reconfigure and actually does reconfigure so many families.

One study involving New York City moms receiving public assistance in the late 1980s and early 90s found that even when accounting for mothers’ histories of mental health issues, substance abuse, domestic violence, and institutional placement, homelessness was by far the strongest predictor that a mother would be separated from her child. While just 8 percent of non-homeless mothers in that study were separated from their children, an alarming 44 percent of those who had requested shelter five years earlier were. “A homeless mother with [no] risk factors is as likely as a housed mother with both drug dependence and domestic violence to become separated from a child,” one paper marveled at these findings.

Sometimes such separations stemmed from an agonizing choice that a parent makes in the interest of a child—to shield a daughter from shelter living, for instance, or to keep her close to her school. Other times living apart from a child was imposed on a parent by relatives or the foster care system. Many separations proved sadly durable: Among the children who were ever separated from their mothers during a five-year period, more than three-quarters remained apart at the follow-up interview.

In the intervening years there have been changes in child welfare policy and certainly fewer children removed to foster care in New York City, yet more recent national research suggests that this pattern of family separations among homeless families persists. “Every study over the years that has looked, both in New York and elsewhere, has found an association between homelessness and family separations,” says Marybeth Shinn, a professor at Vanderbilt University and one of the authors of the study of New York City mothers on public assistance.

Arielle Russell, who lives in Queens and has had children in foster care, says that among her family and friends it’s common wisdom that homelessness and family breakup go hand in hand. “That’s the rules of the game,” she says. “The rules are, once you lose your apartment, ACS [the City’s child welfare agency] comes to your home, disrupting your home, trying to take your kids away, saying that you don’t have a place for your kids to live so you are an unfit mother.”

Russell’s advice to those facing eviction? Keep ACS at bay by finding another family member to take the kids in. “If you get evicted and you have resources,” Russell says, “It’s good to say, ‘Listen, I need you to do this just in case. I need you to take my child for me.’”

‘I Cared About Being with My Mom’

If you want to know what it feels like to grow up homeless in New York City, just ask Marlo Scott, now a wistful and soft-spoken 22-year-old who entered his first New York City shelter as a newborn with his mother. Scott’s mother, now deceased, had three more children and the four of them have been in and out of so many shelters that Scott can’t recall for sure the total, except that it was at least 15. But no matter, he says—from a kid’s point of view, they’re all the same. “They’re all one big room with a bathroom and kitchenette and windows,” he says. “They just have different designs and different names.”

For Scott, shelter living, with its chronic moving and changing of schools and never really having the chance to make friends, was certainly not easy. He remembers always feeling “less fortunate” than the other kids at school, who had “way more privileges,” like, “cable TV, multiple rooms in their homes, and didn’t have to worry about the whole family being home by curfew.”

But that was nothing compared to the times he was apart from his mom, he says. Being in a shelter with her was a world of difference from, say, the times he spent in shelter with his father or uncle after his mother died when he was in the sixth grade. Those were the times he felt truly homeless.

“I didn’t care about being in a shelter. I cared about being with my siblings and mom,” he says.

Scott remembers his mother basking in his accomplishments—bragging to other moms on the block about his report card, sitting down with him to teach him how to write a sentence, and then a paragraph.

She was, he says, a fierce, “mentally tough” woman, with more than her fair share of pain and secrets, which Scott knew had something to do with having a hard life, with having lost her own parents early on, and, like him, having grown up never quite having enough—not enough money, not enough help, not enough love. Sometimes he’d wake in his bunk to see her sitting alone at the shelter table crying in the early morning hours.

She struggled with addiction and cycled through rehab programs the same way she cycled with her kids through shelters. These programs never made space for kids, so sometimes child welfare services would place Scott and his brother somewhere with a relative and his sisters elsewhere, while she worked to get clean. Other times Scott’s mother would pre-empt that progression, sending Scott and his siblings away to various aunts and uncles, saying she needed to “get herself together,” which sometimes meant relapse and other times rehab.

Those times he wasn’t with his mother were what really hurt. “I didn’t like being away from my mother. I knew where I came from when I was around her,” he says. “It’s like she identified me.”

The Fear of Losing Each Other

Research shows that for children, and especially young children, a caring, supportive parent holds the potential to buffer them from the traumas endemic to experiences like homelessness and poverty. It’s a finding that Anna Freud first introduced with research showing that during the London Blitz of 1940, children who stayed with their parents even in the midst of war fared better than those who were sent out of harm’s way to the countryside.

“What we know about trauma and toxic stress is that trusting relationships mitigates those traumas,” says Nishanna Ramoutar, a clinical supervisor at the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services foster care prevention program. “If children live with a caregiver who they love and trust they will fare much better.”

No one knows for sure how many New York City families have themselves seen no better alternative than to splinter apart due to housing troubles. Shelters do not routinely ask if clients have children living elsewhere, and that’s information that parents rarely offer up freely with shelter staff. And in New York, as in many other states, homelessness by itself is not a justification for foster care removal. But in academic homelessness research and in our own interviews with parents and teens who have lived in shelters, a striking theme emerges—the relentless backdrop of fear in the lives of so many homeless families, the common fear that having already lost their homes, they will next lose each other.

“If children live with a [parent] who they love and trust, they will fare much better.”

Marybeth Shinn, of Vanderbilt University, is one of the country’s few researchers who has examined this hidden side effect of homelessness. She is currently involved in a large, national study of over 2,300 families at multiple shelters around the country that is funded by the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development. Shinn found that among families who had spent at least a week in shelter, about 10 percent of parents were living apart from partners, depriving mothers of parenting help and also children of a parent. Nearly a quarter of those families had one or more children under 18 years of age who was living elsewhere. Shinn and her co-authors predict that more separations are likely to occur as the families move through shelter, as research demonstrates that the likelihood of both having a child placed in foster care and informally separating from a child increases the longer a family stays in shelter.

One data match of New York City families from the late 1990s showed that a family’s odds of child welfare involvement more than doubled during the first year of entering shelter.

Today in New York City, you’d be hard-pressed to find a place where the threat of foster care looms larger than in homeless shelters, where about 25 percent of families have a case open with ACS, with just over half of those families receiving services designed to monitor children’s safety while providing supports to their families.

Academic research commonly offers three potential explanations for the high rates of child welfare involvement in shelters. One suggests that the strain of homelessness and shelter living has, as one paper published in Child Welfare put it, a “lasting, detrimental effect on family stability,” exposing and magnifying fault lines that, under better circumstances, might otherwise lie dormant.

Another hypothesis is that the particular pressures of shelter living may themselves be the cause of such fault lines, contributing to abuse and neglect by damaging relationships between parents and children and fueling bad parenting decisions.

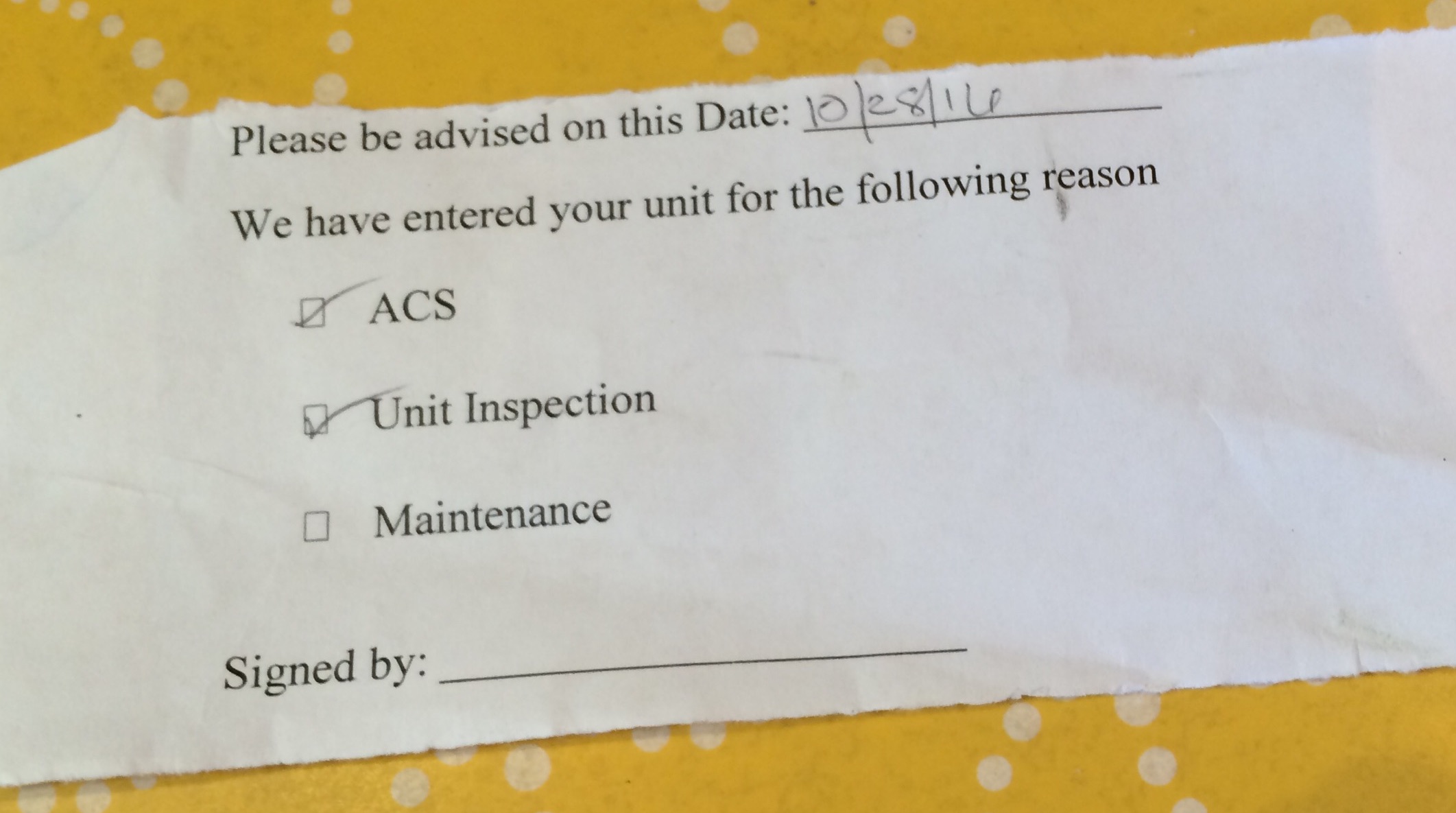

This pro forma document from one Manhattan shelter notifies residents when their shelter unit has been entered while they were away. “ACS” appears as the first reason for entry, more prominent than “unit inspection” and even “maintenance.”

Yet a third explanation is what researchers refer to as the “fishbowl effect”—that in shelters, families are, in essence, parenting in public, where every argument is overheard, every parenting decision witnessed, and where mandated reporters are on site 24-7. “Families are highly visible, both in shelter and afterwards to reporters who may come from different cultural backgrounds and value different parenting styles,” says Shinn.

Late last October, the New York City Council held a hearing examining what went wrong in the death of 6-year-old Zymere Perkins, allegedly killed by his mother’s boyfriend, who had spent some of his young life in a City shelter, and who had repeatedly come to the attention of child protective services. At the hearing, government officials vowed to increase the “contact” and “information sharing” between the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelter staff and ACS. They talked about providing more training to frontline shelter workers about how to spot and report child abuse and neglect—a plan that is now in place.

To some who were there, this sounded like a reasonable response to the City’s obligation to ensure that kids stay safe. One shelter administrator later commented that families may be less likely to have children removed when living in shelters—where ACS knew that their children are being monitored—than if they are living independently. (See “Do Shelters Reduce the Need for Foster Care?” p. 18.)

But others heard this pledge as a call to intensify what they regard as the over-surveillance of homeless families. They worried that it would further empower shelter staff with no social work background to nonetheless act as a de facto extension of child protective services.

“It’s all about monitoring and catching things rather than solving the problem,” said one attorney about the hearing. “Nobody is asking why do 25 percent of families [in shelters] have open cases with ACS, and how to get that number down.”

Judgment and Isolation: A Toxic Combination

Talk to families in shelter and you will hear how they already feel under constant watch, how surveillance and scrutiny feels woven into the fabric of shelter living. “Enter these buildings, and you are making a deal with the devil,” said one mother who lived for many months with her autistic adolescent son in a Manhattan shelter.

“I started to get anxiety after a while. There were little things piling up and piling up where I wanted to burst and lash out at these people and say rude things.”

In interviews with parents and teens living in shelters, we heard story after story of staff at the shelters or, in one case, at the City’s homeless intake center, using the threat of a call to child welfare services as a way to get residents to comply with everything from putting coats on their kids, to getting their school-aged boys to stop roughhousing, to cleaning out their housing unit. For some families, the sense of being constantly monitored created a toxic combination of judgment and isolation, further burdening families’ stress loads and nudging them closer to the breaking point.

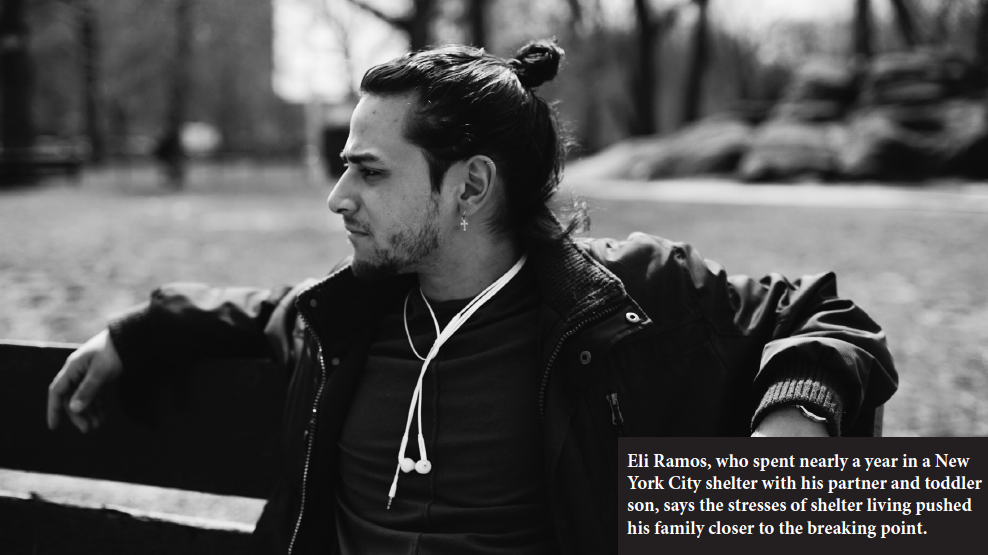

“Whether you have an ACS case or not, it was the same treatment,” remembers Eli Ramos, who spent the better part of his 19th year with his girlfriend and son, also named Eli, in a shelter.

At that well-kept shelter run in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, shelter staff made nightly rounds to make sure all family members were home by curfew, and would also come into the unit at all times of day to do unit checks, often looking into Ramos’s refrigerator and questioning the 2-year-old Eli. “Instead of asking us, ‘How is your son doing, they’d ask him, ‘How are you doing?’ Or they’d ask, ‘Oh, is Mommy doing good?’” says Ramos. “That would really bother us. We felt like they were trying to manipulate Eli. He was only 2 and was the type who would say yes to everything, and so we had to be very careful with them. We had to be super-perfect with everything we were doing, and that caused more stress on us.”

At that time, Ramos was working as a security guard at a nursing home, typically working 40-50 hour weeks, and often the night shift, for $8.75 an hour. When he wasn’t working or sleeping, he was trying to keep up with the relentless stream of appointments required by the shelter to maintain public assistance and other benefits.

Once, Ramos lost his job for calling in late so that he could make these appointments. Other times, when he prioritized being on time for work over the appointments, there were weeks and even months when the family’s benefits would be on hold until he found time to trek to the public assistance office. This had consequences not just for the amount of food in the family’s cupboards, but also for how closely shelter staff scrutinized them. A nearly empty refrigerator never failed to arouse staff’s curiosity, he says, something that would not have bothered him so much if it had come with an offer of help. Instead, Ramos lived with the feeling that he and his partner alone were responsible for finding their way out of shelter, and that if they fell short on money for food or Pampers, it was best to hide it—something that did not benefit anyone.

“I started to get anxiety after a while,” he says. “There were little things piling up and piling up where I wanted to burst and lash out at these people and say rude things.”

Instead, he and his girlfriend began to turn on each other. “We were continuously arguing over little stuff, and our son used to watch it and that put a toll on him.”

An Isolation that Felt Suffocating

Ramos saw his son turn from a happy-go-lucky toddler to a conflicted one—still content when he was at the playground, angry when it was time to return to long days alone with his mother in their one-room shelter unit. Visitors weren’t allowed in the units, so playdates, even with other kids in the shelter, were not even a possibility. The isolation felt suffocating.

Both of young Eli’s grandmothers wanted to help, but as with many families in shelter, Ramos’s shelter placement was far away from the family’s former neighborhood in the Bronx, where they used to live with Ramos’s mother, and where little Eli’s other grandmother also lived. For the grandmothers to visit, they had to travel over an hour by train, a trip made somewhat pointless by the shelter’s no-visitor policy that restricted them from entering the family’s unit once they got there. There was one room where all families could visit, Ramos remembers, but that was often noisy and sometimes filled with cursing and arguing—not a place where he wanted his mother and child to spend time together.

Leaving little Eli with them for a night here or there would have given the entire family a much-needed respite, but if there was a way for that to happen, no one told Ramos about it. Instead, Ramos was under the impression that overnight visits were forbidden by shelter rules. “That would have been an ACS case right there,” he says.

So for the year they spent in shelter, Ramos and his family lived deprived of what a recent report by the New York City Independent Budget Office calls a family’s “networking and social capital resources”—some of the most valuable resources available to struggling families.

When the City’s Department of Homeless Services (DHS) moves families away from the communities and then institutes “a ‘no visitor’ policy [in shelters],” said Stephanie Gendell of Citizens Committee for Children in testimony at the City Council hearing on the Perkins case, “families are unable to create a new social network in their new community. Combined with the curfew, it is nearly impossible for adults and children in shelter to maintain connections to their social supports and networks.”

Social isolation, Gendell points out, is a well-documented risk factor for child abuse and neglect, and “the exact opposite of what we want for families struggling with the trauma and stress of homelessness.”

Life in a Cloud of Fog

When Ramos thinks of his time in shelter, he remembers it like living in a cloud of fog, “like I wasn’t free.”

It felt that disconnected from everything that came before it and everything that would come after, an alternate universe where all his neighbors were people who had been evicted and, some mornings coming home from the night shift, he could feel and see their strain and hopelessness—the yelling through the walls, the babies crying, the sound of a toddler who wouldn’t come when called being dragged, the kids eating candy for breakfast.

Ramos understood why ACS felt like such a looming, threatening presence in the shelter life. Families needed help. But too often instead of a lifeline, parents received scrutiny and judgment.

The restrictive shelter rules and regulations only fueled the fire. TV screens could be no bigger than 19 inches. Decorations to make the shelter feel like home—even tiny figurines—weren’t permitted. Even the most intimate of living details felt under scrutiny. When Ramos and his girlfriend, who was pregnant with their second child, pulled together the two twin beds to make one bed for them together, shelter staff told them that was not allowed. “It was like, ‘If you’re in our house then we can do whatever we want to you,’” remembers Ramos.

Over time it became too much. Ramos began to question why he was going through all this. The easier thing, he knew, was to just give up, break up the family. He could return to live with his mom in her one-bedroom apartment, and his partner and son could squeeze into her mother’s already overcrowded home. Maybe being apart was better than being together in shelter.

“It got to the point where I was saying, ‘I’ll go back to my mom and you go back to your mom’s house,” he says of a path they ultimately didn’t take. “The stress load caused us to not feel for each other.”

The Most Durable Effect of Homelessness

Families that splinter apart while homeless tend to view these separations, as they do their housing situation—as something temporary, the best in a parade of bad options. Some families who subsequently secure stable housing are indeed reunified, and long-term housing vouchers have been found to be especially effective at reducing separations. (See “Long-term Housing Vouchers Help Families Stay Together,” p. 13.) But other studies find separations to be one of the most enduring effects of time spent homeless.

Once kids and parents are split up, homelessness makes it hard to reunify. Parents who do not have full custody of their children are often ineligible for housing, public assistance, and other benefits, and so may be unable to create homes fit for their children to return to. For parents with children in foster care, homelessness makes it difficult to carry out prerequisites for reunification, such as having in-home visits before children can return home.

In New York City, homeless mothers with children in foster care can receive priority for public housing. But if they reunify with their children while living doubled up in a friend’s or family member’s home prior to receiving a housing placement, they lose their eligibility, forcing them to choose between living with their children or keeping their priority in the long line for public housing.13

But some researchers believe that the persistence of separations among homeless family members has even deeper roots. In the study of New York City mothers who had separated from children, a surprising 40 percent of those mothers began living apart from their children not during their time homeless, but after leaving the shelter system. These separations typically occurred not because child welfare authorities or a court mandated it, but because family members themselves decided it was best, lending more credence to the theory that something about shelter life itself—with its lack of privacy, isolation, intense scrutiny, and restrictive rules—can erode a parent’s authority and chip away at familial bonds.

“I couldn’t tell how stressed out I was until I actually moved.””

“I get in trouble every time my children act up in the lobby,” one single mother with young boys told us about shelter living. “They try to dismantle the family as a unit.”

We Needed More Guidance

Ramos’s family narrowly avoided separating. They stayed together to see the birth of their second child—a girl, this time, one of the close to 2,000 babies born to families in shelters that year. Soon after that, the family was assigned public housing in East Harlem.

Now, almost three years and a third baby later, Ramos works as a family advocate at one of the City’s Mental Health Association Family Resource Centers, where he supports other families navigating their own crises. When Ramos thinks back to that time they spent homeless, he says, “I couldn’t tell how stressed out I was until I actually moved. We needed a little more help. We needed more guidance.”

He has no photos of the shelter that was his daughter’s first home; the year that his son was 2 remains largely undocumented. After all, that was the year that his young family endured so much stress they came close to splitting apart, and that, he says, is heartbreaking. It’s something he’d like to forget.

Read the full report: Adrift in NYC: Family Homelessness and the Struggle to Stay Together